Invisible women

Most women (64%) received into prison are serving short prison sentences of less than 12 months. However, the small minority serving very long determinate or indeterminate sentences are often overlooked in advocacy debates and policy, meaning their experiences are not fully recognised, a new briefing published by the Prison Reform Trust last Friday (19 November, 2021) has revealed.

The briefing has been produced in collaboration with 16 women serving indeterminate sentences as part of the Prison Reform Trust’s Building Futures programme, a five-year project funded by the National Lottery Community Fund to explore the experiences of people who will spend 10 or more years in custody. It is the first in a series intended to shed light on the distinct experiences of these often ‘invisible women’ serving long determinate and indeterminate sentences.

Whilst women serving an indeterminate sentence continue to be a small minority of the total population of women in prison, the number has grown from 96 in 1991, to 328 in 2021. As a proportion of the women’s population, women serving indeterminate sentences declined overall from 6% to 4% between 1991 and 2005, before nearly doubling from 6% to 10% between 2005 and 2013 and remaining roughly consistent since then. For anyone serving an indeterminate sentence, the pains of imprisonment are exacerbated by the uncertainty and powerlessness which can commonly come to define their time in prison.

This briefing highlights the far-reaching consequences of a lack of specialist, gender-specific, trauma informed provision for these women. Most women serving long prison sentences will have extensive histories of trauma and are often victims as well as perpetrators. In a study of women serving life sentences, 60% reported histories of sexual abuse, 80% had experienced physical abuse and 54% reported both sexual and physical abuse. Women lacking specialist support can feel isolated in their trauma; those serving long sentences are more exposed to repeat traumatisation.

The report focuses on three main issues:

- The impact of previous trauma

- Familial relationships and reproductive capacity

- Progression support

Trauma

For women serving indeterminate sentences, the nature of the sentence and the uncertainty and fear associated with it can bring about distressing and destructive emotions, leading to self-harm and suicide attempts. Regular readers will be aware of the very high rates of self-harm among women in prison.

Women lacking specialist support can feel isolated in their trauma, and for those serving indeterminate sentences, concerns regarding risk and progression may prevent them from reaching out to staff for support. Particularly for women serving long sentences, who are exposed to these environments for such a lengthy period, the long-term consequences may include social withdrawal and emotional numbing, which may cause issues for life in the community post-release. Here’s the view of one woman interviewed for the report:

“There seems very little support when we experience a death in custody, and or serious self-harm. I have experienced approximately 10 deaths in custody in the years I have been in and they are never easy to deal with.”

The introduction of Trauma-Informed Care and Practice has been welcomed by many as having the potential to, if properly implemented, ameliorate many of the traumas experienced by women in prison. However, its implementation has been to varying success, with some oversimplification of what it means to be properly trauma-informed, tending to revolve around cosmetic improvements to prison spaces. The report found that in practice the security function of prison often takes precedence over care.

Family Contact

Losing contact with children is one of the most distressing elements of imprisonment for women serving sentences of all lengths, but women serving long sentences are likely to be impacted in particularly stark ways. Imprisoned women suffer psychological and emotional pain as a result of losing contact with their children, damaging their mental health and their ability to engage with the regime and progress through their sentence. Attempts to maintain contact with children can also be hard, as the process of separation that takes place at the end of every face-to-face visit causes extreme distress for both mothers and their children.

Additionally, women are often held far away from their home towns, with the average distance between home and prison being 63 miles, but with a significant number being held more than 100 miles from home. The practicalities of the cost and time of organising visits means many women also struggle to maintain regular face-to-face contact with their children. This can create scenarios in which women’s family visits can be counted on one hand, even as time served creeps into double digits as one person interviewed for the study shares:

“I saw my mum about four times in fourteen years. I saw my son twice. I saw my sister about four times and I saw my dad more. When I went to another prison I was about 200 miles away from home so my dad only came once at Christmas.”

Progression

For anyone serving an indeterminate sentence, uncertainty and frustration commonly come to define their time in prison. Feelings of powerlessness can translate into hopelessness and helplessness for women who perceive they lack control in their lives and cannot plan for the future.

People subject to these sentences have to be consistently and actively engaged in the rehabilitative process to demonstrate their risk has reduced. In some instances, this preoccupation with risk reduction may be costly. For instance, women may have to relocate to a prison further away from home to access interventions or courses on their sentence plan, to the detriment of contact with family.

As is common for people serving indeterminate sentences, concern for being viewed as a ‘poor coper’, for fear of what this could mean for their progression, can mean women are unwilling to access support. Being vulnerable is often equated with risk and the need for care with the need for continued confinement or monitoring:

“When you’re serving a sentence like that, you’re watched all the time and everything is documented. Anything could be seen as going wrong or ‘high risk’ when actually you’re just having a shit week. But you can’t tell anyone because you’re frightened that it’s going to get used against you two years down the line when you sit parole.”

Conclusion

The report concludes by calling for a distinct approach for women serving long sentences. Forthcoming publications under this programme will share the views of women in this situation themselves on what improvements should be made.

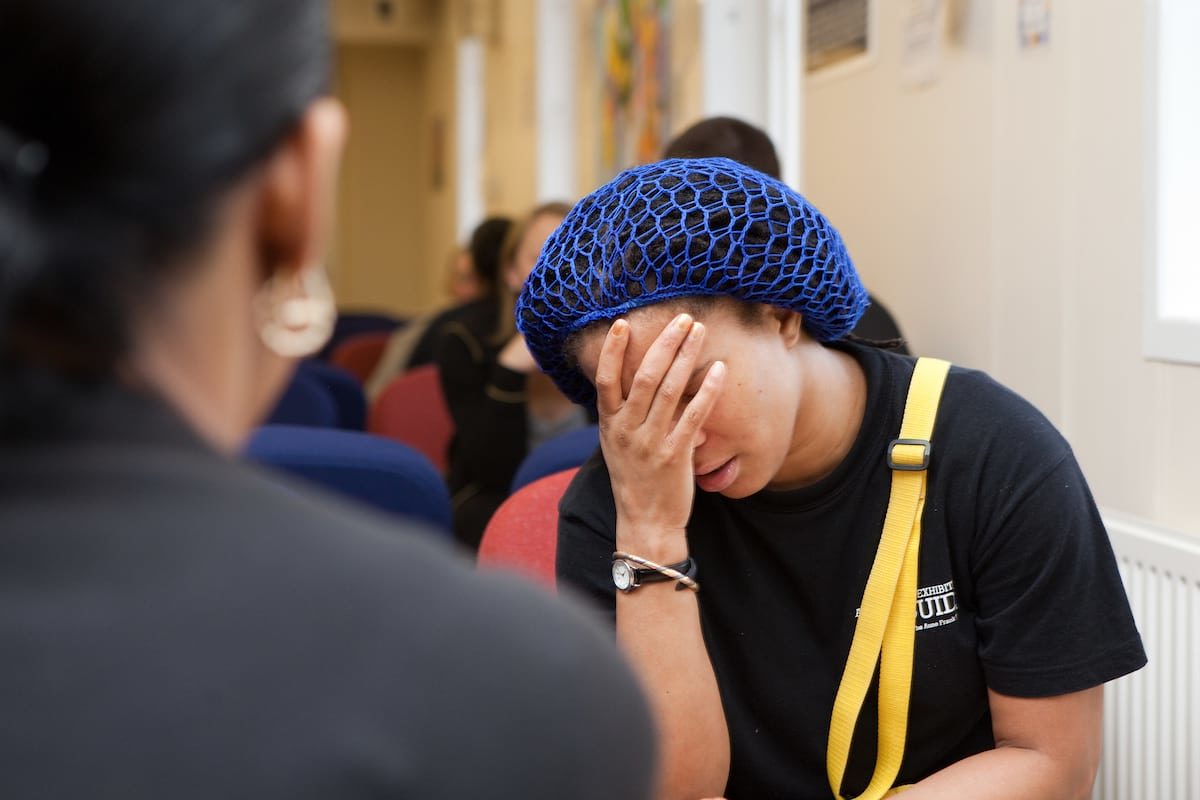

Thanks to Andy Aitchison for kind permission to use the images in this post. You can see Andy’s work here.