Tackling complex needs

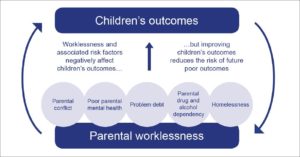

A new (18 September 2015) report from the Institute for Public Policy Research: “Breaking boundaries: Towards a ‘Troubled Lives’ programme for people facing multiple and complex needs” calls for the government to launch a new programme to deliver a coordinated response to the 1/4 million people who experience multiple problems such as addiction, homelessness, reoffending and poor mental health.

“Breaking boundaries: Towards a ‘Troubled Lives’ programme for people facing multiple and complex needs” calls for the government to launch a new programme to deliver a coordinated response to the 1/4 million people who experience multiple problems such as addiction, homelessness, reoffending and poor mental health.

IPPR draws on the success of the Troubled Families programme which it says has been successful in pioneering integrated support and in producing savings by reducing demand for crisis-led services. A relatively small pot of central funding has generated additional financial commitments from local areas and galvanised agencies to set up local “invest to save” partnerships.

The report is supported by the Lankelly Chase Foundation which has funded a lot of work into complex need including the first large scale mapping of the extent of this problem in England.

[divider]

A proactive approach

IPPR put forward the same rationale that was advanced to establish the Troubled Families programme; that the current response to people with complex needs is still largely reactive and uncoordinated, mainly consisting of expensive crisis services rather than preventative work.

The report’s authors, Clare McNeil and Jack Hunter, review recent public service reforms and conclude that most have failed to give local areas the necessary powers, responsibility and accountability to improve the lives of the most excluded people, with the exception of Troubled Families which has galvanised local areas to bring existing agencies to work together more effectively, rather than adding another layer of intervention onto an already complex system.

IPPR recognise that aspects of the Troubled Families model are flawed and government claims about the results and savings achieved by the programme are dubious. However, they say that the programme is having some success in improving integration where previous strategies have struggled.

The report argues that the core elements of any successful approach to improve the lives of adults with complex and overlapping problems should be:

- An area-based, decentralised approach, not large-scale national programmes;

- National priorities set by central government, but local responsibility and accountability for design and delivery; and

- Integrated funding, commissioning and delivery for person-centred support and clear incentives for wider systems to change.

[divider]

A new approach to payment by results

The report’s authors acknowledge the benefits of payment by results (which is the commissioning approach used for the Troubled Families programme):

PbR schemes can focus efforts on specified outcomes rather than processes or inputs, and can help clarify accountabilities because they hold local authorities or providers to account for the delivery of specified outcomes. With the Troubled Families programme, PbR provided incentives to stimulate cooperation between local agencies and helped attract additional local financial commitments.

However, they also note that PbR is difficult to use for individuals with multiple and complex needs:

PbR schemes are most effective when outcomes are easy to measure and can clearly be attributed to a provider’s intervention. However, effective interventions for this group rely on coordinating support from a range of different agencies, and progress can be affected by factors beyond the control of services, such as wider government policy and economic conditions.

Their solution is to recommend that instead of the PbR element of the programme being linked to achieving individual-level outcome-based payments, area-level outcomes should be adopted. They argue that this retains the incentives for local cooperation provided by the Troubled Families PbR model, but removes the need for artificial or forced results from interventions with individuals.

Specifically, they suggest that upper tier local authorities should be required to show reduced demand for expensive crisis care services after one year of the programme.

In my opinion, this reinvestment approach makes sense for PbR schemes which seek to tackle entrenched social problems with client groups almost inevitably made up of individuals with a wide range of different needs.

[For more research on payment by results and families/individuals with complex needs, check out this section of my PbR resource pack.]

2 Responses

Do you know if this new approach leaves room for local recovery movement’s to develop services that are not a specialized service. In the last two years we have noticed an increase in local recovery groups turning themselves into CICs and delivering community focused recovery activities outside of commissioned specialized OST services.

Hi Tony

This is just a proposal from the IPPR Think Tank, not policy

Best Wishes

Russell