This is the second in a three-part blog series from Tom Gash looking at the global challenges that crime will bring to developed countries in 2017. Many readers will already know Tom from his book: Criminal: the truth about why people do bad things which successfully deconstructed many of the myths about crime and offending promoted by politicians of all persuasions. You can catch up with Tom on Twitter: @Tom_Gash

Crime changes are not the main problem

In 2017, shifting patterns of crime will need to be addressed – but the real issue is how politicians and public officials manage their way out of messes usually created by others.

In part one of this 3-part blog, I put forward some thoughts on how shifts in patterns of crime might affect governments in the coming year. But the truth is that many countries will still be predominantly focused on coping with the consequences of past policy decisions and tightening budgets.

In 2017, there will be few countries whose criminal justice budgets are rising in real terms. Canadian federal spending is continuing to fall slowly and slightly in both the Department of Justice and Department of Public Safety. Fathoming U.S. trends is a challenge given its multi-layered public safety governance but there too there are no signs of major spending increases.

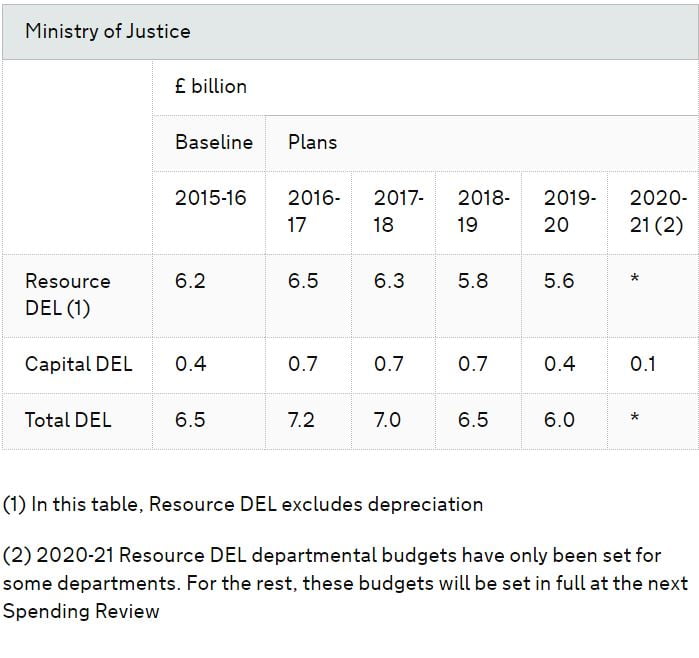

The UK will likely see flat spending in real terms but this is after a sustained period of spending reductions. Home Office budgets fell around a fifth or nearly a quarter in real terms between 2010-2015. The Ministry of Justice suffered even more, signed up to cuts of nearly a third in real terms in 2010-15 – which it didn’t quite achieve and now won’t have to. The image below shows the MoJ settlement at the 2015 spending review:

New Zealand seems to have ended its long-term ramp-up of officer numbers and with a stabilising prison population spending is unlikely to increase there either. One outlier is Australia. Most states there will be spending more in 2017, both to fund the build and management of prisons that are bursting at the seams, to protect police numbers and kick off new projects on issues that remain of higher public concern than countries more deeply affected by the post-financial crisis crash. Austerity will hit Australia sometime – but for now everyone should look at the UK to understand what can and can’t be done when belts tighten sharply.

As noted in part one, falling cash comes at a time when demand from certain crime types is increasing but other crime types will likely decrease. In truth, of course, justice system demands are not driven solely by underlying crime patterns. Policy and practice across the justice system drives volumes – with policing strategies (and numbers), sentencing, bail policies, drugs laws and stances on courts and probation administration all playing their part. I think it’s now fair to say that most English-speaking developed countries are creaking at the seams as a result of past policy decisions – and only a few European states, such as the Netherlands, have shifted their policy settings in a way that supports, rather than fights against, budget reductions.

Prisons

Correctional services sit at the downstream end of what we call a justice ‘system’ but which almost everywhere is still managed as a discrete set of separate – and sometimes competing – institutions. Unfortunately, prisons have rarely been resourced to deal with the increased workload that more police and tougher sentencing have gifted them – so are now under intense strain.

US, New Zealand, and UK prison numbers have all stabilized but after decades of expansion, driven by increased police activity and tougher sentencing. Australia is still on a rapid trajectory of increasing prison numbers, despite falling crime, while the picture in Europe is more mixed.

Few expansions have been well planned. The impact of sentencing and other policy changes is not easy to predict – but the truth is that the accelerated prison build programmes, use of inappropriate accommodation and overcrowding are all signs of poor planning. These problems have contributed to violence, self-harm, reductions in rehabilitative activities and rising health costs for aging inmates – management headaches that are exacerbated by country-specific issues relating to gangs, extremism, and new psychoactive substances.

The prison environment has become a difficult place to work with rising staff to inmate ratios but few improvements in pay or job satisfaction. Recruitment shortfalls are an inevitable consequence, particularly in countries where private prisons have created fiercer wage competition and reduced job security.

Probation

The boom in prison was accompanied by a boom in ‘community corrections’ (community sentences, probation and parole), though US probationer numbers at least are now falling. Under strain, many services became light touch and focused primarily on ‘risk management’, with limited funding for rehabilitative work except in pockets and for higher risk offenders.

Some countries now face additional strains. The UK is still reeling from the impact of an excessively hasty and probably ill-conceived set of probation reforms that simultaneously cut budgets, increased caseloads, and brought in providers who had never done the job before.

Falling youth crime

2017’s only good news in corrections may be a continued fall in the number of juveniles incarcerated. The phenomenon of falling youth crime and incarceration is not well understood, however, and learning about it must be high on the agenda this year for anyone who wants to ensure the success is sustained.

Courts

In the first post in this series, we talked about sex: sexual offences are dominating the work of higher courts everywhere due to their complexity and because defendants are still far less likely to plead guilty than for other crimes. In some (but by no means all) places, the shift has led to case backlogs in the higher courts, longer waits for justice and an increased the number of ‘cracked’ trials.

Yet higher court backlogs often sit alongside clear over-capacity in the physical court infrastructure, particularly in lower courts, where broader caseloads are often falling. The UK is closing down underutilised facilities rapidly and other countries will soon have to follow in order to free up resources to invest in new technologies and the specialist court facilities that appear to offer benefits for specific offender cohorts, such as mental health patients and drugs users.

Police

Police forces face their own challenges. They are upstream of prisons and courts but officers everywhere still feel like they are on the receiving end of decisions made elsewhere. The main reason police feel overwhelmed appears to be the ongoing demand for support from the public even where no crime has taken place – and where problems are more properly dealt with by mental health or social services. Only a few of the best police forces have a good understanding of where demand truly comes from and how to prioritise it. And fewer still have yet been given the political support needed to make the tough prioritisation decisions that falling budgets will necessitate – particularly in countries that maintain antiquated and in some cases generous officer terms and conditions.

Leicester’s attempt to respond to attempted burglary cases selectively, was criticised by the Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC), Sir Clive Loader. More positively, Northumbria’s PCC, Dame Vera Baird, has publicly backed giving victims the option of not having a physical police response to car crime. Such tough choices are needed – so the politics of policing is set to remain in the spotlight this year, both for this reason and due to ongoing debates about police legitimacy, which will play out most starkly around issues such as armed response, stop and search, and undercover policing tactics.

Conclusion

Overall, 2017 feels like another year in a period of transition within justice systems across the developed world. It is a period when countries will have to work out ways of dealing with the legacy of decisions made some time ago but perhaps no longer affordable given competing priorities such as healthcare for an aging population and limited public appetite for higher taxation. In part three of this series (published next Monday), we will look at what countries can – and must do – to manage their way out of these tricky situations.

Blog posts in the Criminal Justice category are kindly sponsored by Get the Data which provides Social Impact Analytics to enable organisations to demonstrate their impact on society. GtD has no editorial influence on the contents of this site.