This is the sixth in a short series of posts on the RSA’s Future Prison project which sets out a blueprint for the modernisation of our prison system.

The rehabilitative workforce

We know that there are not enough prison officers currently staffing our prisons.

NOMS is currently struggling with a particularly vicious circle:

- Budget cuts led to big reductions in staff leading to:

- Unsafe prisons which encouraged more staff to leave and

- Made it difficult for new inexperienced officers to learn their job safely, resulting in

- Many of these leaving or not passing their probation period.

Despite NOMS engaging in a “full throttle” recruitment programme in 2015 which brought on board 2,250 extra prison staff, this resulted in a net game of just 440 officers because of the growing numbers of staff leaving the prison service.

The House of Commons Justice Committee was so concerned by the situation this May that it made a formal request for quarterly reports from the MoJ and NOMS for the rest of the parliament on the latest prison safety statistics (including those not routinely made public) and a recommendation that the MoJ and NOMS jointly produce an action plan addressing prison safety.

The RSA report acknowledges these very real and current staffing difficulties before going on ask one of the toughest questions of the whole Future Prison project:

What should the future prison workforce look like and what skills are required?

The report notes that currently prospective prison officers do not require 5 GCSEs and until recently received only 6 weeks generic training (now increased to 10 weeks) – some of the lowest levels of training in the world.

The RSA highlights the fact that although many officers and operational staff still see their work as a vocation and are passionate about the potential role that prison can play in changing people’s lives. However, it also emphasises that the changes made since 2013 through benchmarking have not been welcomed by many staff with many feeling that the outcome – as well as fewer staff and lower staff to prisoner ratios – has been a deskilling of the prison officer role and a squeeze on middle grades.

Current training

Prison officer training aims to provide new prison officers with the core skills and knowledge they need to begin their prison careers. Delivery is shared between prisons, a central training centre – the Prison Service College Newbold Revel – and/or one of 15 local training centres.

A new officer will be on probation for 12 months and be expected to complete the CCNVQ Level 3 within a year of completing the eight-week course which covers:

- The Purpose of the Prison Service/Role of a Prison Officer/Professionals Attitudes

- Interpersonal Skills

- All aspects of Security and Searching

- Understanding Self Harm

- Diversity

- Violence Reduction

- Substance Misuse

- Radio

- Interviewing and Report Writing

- Placing a Prisoner on Report/Adjudications

- Escorts

- Restraints

- Heartstart

- Public Protection

Many prison officers and operational staff work alongside a range of agencies – health, education, substance misuse services and charities – operating inside the prison. While some prisons make this work well, there can be tensions between the reasonable demands of agencies and officers’ day-to-day operations.

Much of this comes down to what is and what is not considered ‘core business’ as well as a lack of staff ownership of key areas of work and intervention.

Shaping the future prison workforce

The Future Prison project intends to explore what kinds of skills and competencies are needed to strengthen people’s chances of rehabilitation, their current skills base and the extent to which training and development is fit for purpose and/or may need to change in relation to a greater focus rehabilitation.

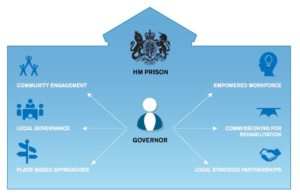

This includes exploring the attitudes of staff to their roles, how they would like to see them change and what they hope to look for in their new more autonomous prison leaders.

The report sets out a number of key questions about the rehabilitative workforce:

- What is the range of skills needed to support rehabilitation and to what extent are the current prison workforce recruited and developed on this basis?

- If there is greater autonomy at the top, does this suggest a change of role also for the workforce and a new relationship between staff and prison leaders?

- How could future prison leaders strengthen rehabilitative culture and support their workforce in reducing risk and keeping staff and those in custody safe?

- What kinds of capabilities and skills are needed and what is the relationship between this and greater autonomy and role of other agencies working within prisons?

- What support do staff need from outsiders to help them in their role and how would staff be heard by new boards?

- How can the workforce benefit from these changes and what challenges and obstacles lie in the way, including developing better progression routes within and without the prison service?

- How can becoming a prison officer be a job of choice for more people so that prisons are able to recruit, retain and develop a stronger and valued workforce?

2 responses

Really interesting…Safe Ground have been running a therapeutic group work programme with Prison Officers for 2 years and we have lots of feedback from participants about their role, t and cs and reasons for joining the service. I am FRSA and should make use of it to get involved with this. Thanks as ever, Russell, charlie

Thanks for your comment, Charlie. I’m sure Rachel O’Brien would be keen for your input. It’s an obvious point that without good staff, the prison reform programme has no chance of success.