What works in reducing reoffending?

One of the spin-offs of Transforming Rehabilitation, the government’s part-privatisation of the probation service was the MoJ’s launch of of the Justice Data Lab (JDL) in April 2013 which was set up to encourage analysis of the effectiveness of reoffending initiatives.

The JDL has always published its findings on the second Thursday of the month and looking at its analysis of the work of the P3 Link Worker Service published on 9 January made me think it was time for an update on the knowledge the JDL has generated.

By the way the P3 Link Worker scheme, which works with clients to help them build skills and support networks, was found to be effective at reducing reoffending. Offenders participating in the scheme had a lower one-year proven reoffending rate, and lower offending frequency, and took longer to reoffend compared to a matched comparison group.

How the Justice Data Lab works

The purpose of the JDL is to allow any organisation that works with offenders to find out the impact of their service on reoffending.

To use the service, organisations simply supply the data lab with details of the offenders who they have worked with and information about the services they have provided.

The justice data lab then supplies aggregate one-year proven re-offending rates for that group, and, most importantly, that of a matched control group of similar offenders.

Findings

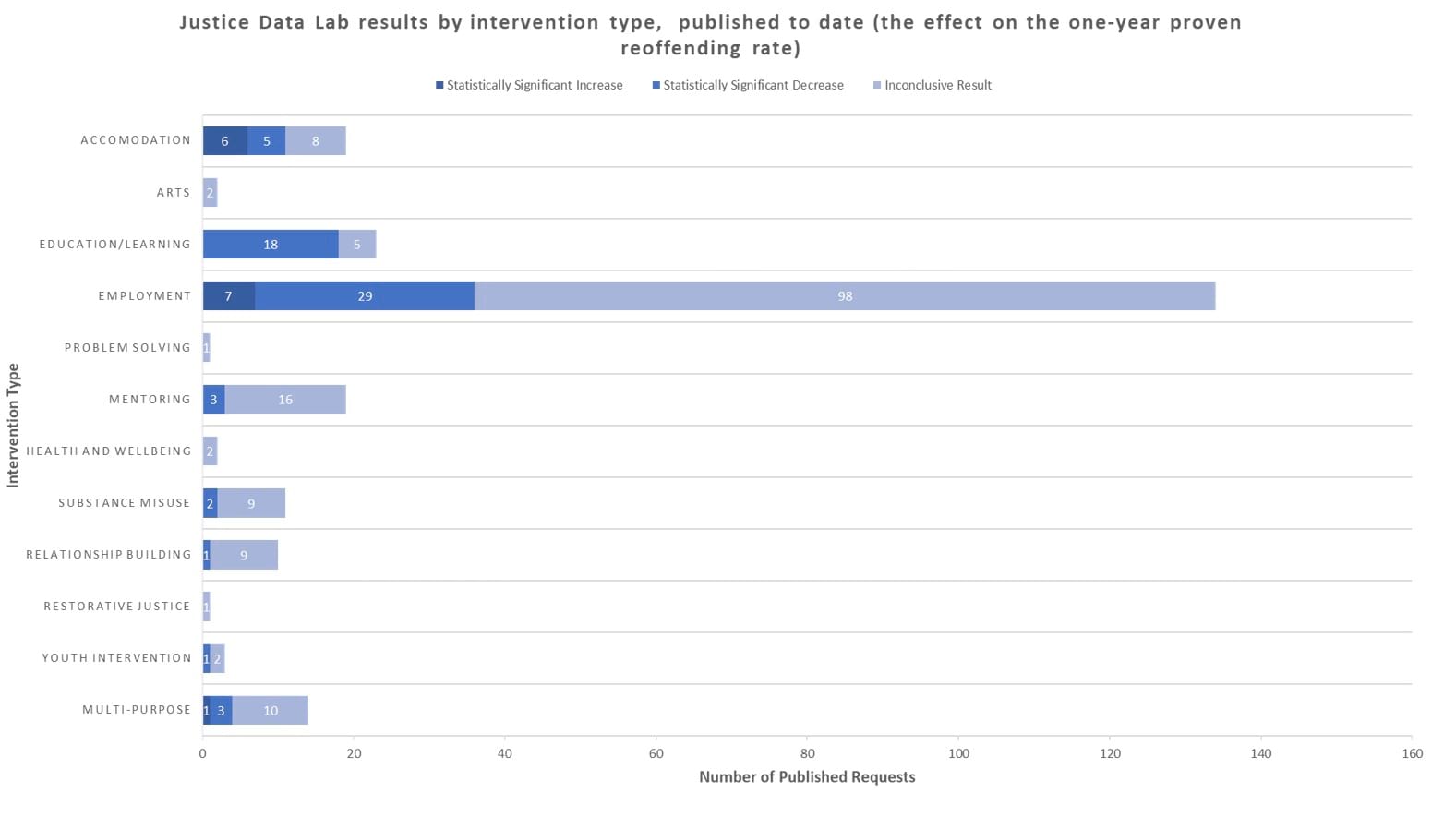

Between the launch of the Justice Data Lab service on 2 April 2013 and 9 January 2020, the JDL has analysed the effectiveness of 237 separate interventions. The types of intervention analysed were:

- Employment schemes (134)

- Education/learning programmes (23)

- Accommodation support (19)

- Mentoring (19)

- Multi-purpose (14)

- Substance Misuse (11)

- Relationship-building (10)

- Youth intervention (3)

- Arts (2)

- Health and wellbeing (2)

- Problem solving (1)

- Restorative Justice (1)

Outcomes

In terms of one year reoffending rates: in 163 of these schemes, it hasn’t been possible to say whether the intervention has increased or decreased re offending rates. However, there are 62 interventions which the MoJ has been able to prove successful and 14 programmes which appear to have resulted in an increase in reoffending.

Of the 62 examples where there was a significant decrease in reoffending, almost half (29) were employment schemes (mainly NOMS CFO) and more than one quarter (18) were education/learning schemes. Of the other interventions proven to be successful: 5 were accommodation schemes, 3 mentoring programmes, 3 “multi-purpose”, 2 substance misuse, 1 relationship building and 1 youth intervention.

Conclusion

It’s a shame that the evidence base doesn’t include more examples and give us a more exact idea of what works in reducing reoffending after nearly seven years of operation. Of course, this is not the Data Lab’s fault — it can only analyse the interventions which are submitted to it.

Nevertheless, the need for an effective evidence-base has never been more needed. Funding remains restricted and it is important that we get maximum impact out of all available resources.

Given the recent discussion about the value of our current suite of accredited programmes, which are in the process of being outsourced to new Probation Delivery Partners, it would be interested to see HMPPS submit these for evaluation in terms of their impact on reducing reoffending.

If you would like to peruse these figures in more detail, all JDL stats can be found here.

2 responses

waste of time and money

I think this tells us that the Data labs is plainly an example of bad science. Single interventions should not be attributed to re-conviction outcomes because individuals operate within an ecosystem of services, their community and personal networks. There will always be far too many subjective unknowns about an individual and uncontrollable environmental factors to make this useful. Although these results might a loose indicator of performance – it is only ever a loose indicator and I’d take all of the results with a pinch of salt. Most services are good, the problem is that people fall between the gaps in services and that the right services are not available at the right time in the right place with the right use of resources. To reduce this to an algorithm actually promotes false science because all successful services are person centred and deliver tailored responses to the risks, needs and responsivity of individuals. There are some services which are better than others but we will achieve the best results by improving all services within local systems within a context of whole system working rather than fixating on strategic levers for high level political vanity projects.