The Cambridge Crime Harm Index

Traditionally, we’ve defined the crime rate by counting the total number of crimes.

This is misleading to say the least.

All crimes are not created equal — we would happily see the number of shoplifting offences double in return for a drop in 25% in the murder rate.

Renowned US criminologist Lawrence Sherman has been campaigning for a change in this approach since 2007, advocating as a replacement the creation of a Crime Harm Index.

Now he has joined forces with colleagues from the Cambridge Institute of Criminology, Peter Neyroud and Eleanor Neyroud, to develop a UK version — the Cambridge Crime Harm Index.

(Peter Neyroud is an ex-Chief Constable of Thames Valley and well worth a follow on Twitter: @pwneyroud.)

The Cambridge Crime Harm Index: Measuring Total Harm from Crime Based on Sentencing Guidelines was published in; Policing: A journal of Policy and Practice on 3 April 2016 and I’m delighted to say you can download it for free in its entirety.

A theory of relativity

The basic principle for a meaningful measure of crime is to classify each crime type according to how harmful it is, relative to all other crimes.

The authors set out to demonstrate how a crime “count” report can be supplemented by a crime “harm” report to develop:

a low-cost, easily adoptable barometer of the total impact of harm from crimes committed by other citizens, as reported by witnesses and victims.

Interestingly, the authors argue that only crimes reported by victims or witnesses should be “calibrated” (i.e. their relative harm defined). The Cambridge Crime Harm Index (CCHI) excludes proactively generated crime detection by police and organizational victims. The reason for that exclusion is that such crime reports (with 100% clearance by arrests) do not reliably measure harms experienced by the population.

Working only with offence types that police count reactively on the basis of citizen reports, the CCHI multiplies each crime event in each crime category by the number of days in prison that crime of that category would attract if one offender were to be convicted of committing it.

To do this, the authors decide to use the starting point for sentencing set out in the sentencing guidelines — that is, not taking into account any mitigating or aggravating factors. They argue that whether a first time offender or a serial killer murders someone:

the murder creates the same harm to the victims, his or her families, and communities.

The actual punishment each offender ‘deserves’ to receive is a very different question from how much harm the crime has caused. The concept of harm is separated out from that of culpability.

Three key criteria

Coming up with a meaningful Crime Harm Index is a complex and challenging endeavour and the authors set a three-pronged test of suitability which the CHI must pass:

- Does the metric reflect the resolution of conflicting viewpoints by a process adopted by a democratic government reflecting the will of the people (the ‘democracy test’)?

- Does the metric provide a reliable measure that can be consistently applied to each unit of analysis — time, place, people — with the same results for the same levels of harm (the ‘reliability test’)?

- Is the metric readily available at virtually no cost to be adopted without any new budgetary appropriation (the ‘cost test’)?

The difference between crime count and crime harm

This is an important contribution to the crime debate because how we count crime matters.

Not just in terms of media headlines, but in how we assess risks, allocate resources and hold Home Secretaries and Police & Crime Commissioners accountable.

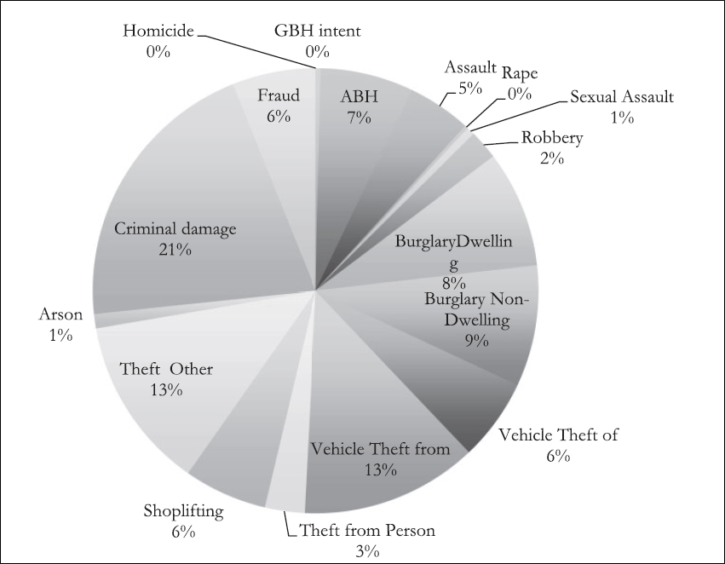

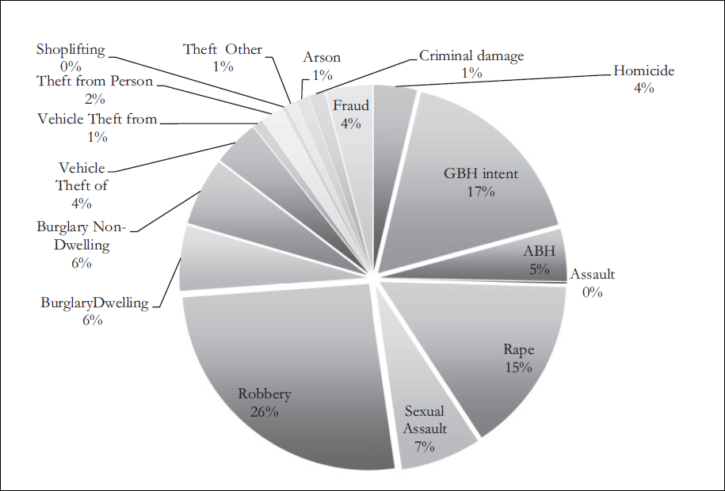

This contention is best demonstrated by the graphics below which shows the UK crime figures for 2002/3 treated in two different ways; firstly, the traditional approach of counting the number of different types of offences, contrasted with the second graphic which uses the Crime Harm Index.

Crime count for 2002/3

Crime harm index for 2002/3

Conclusion

As you can see, the Crime Harm Index encourages much more attention to be paid to robbery and crimes of violence than a simple crime count.

The authors contend that the concentration of CHI values in “harm spots” (that can supplement the ‘hot spots’ of crime counts) helps effective policing and the targeting of important crimes such as repeat domestic violence.

They argue that the CHI rings a clarity to the crime debate while acknowledging that this clarity may not always be welcomed by those in power or in the media who would find it harder to shape a story about whether crime is better or worse to suit their own agendas.

2 Responses

Interesting, but Im not entirely sure it’s a good idea….The fact is most crime is of a kind that doesnt do much harm or greatly worry people. I’d be concerned that the new measure which you show graphically might be counter-productive – might seem to say (however often one explained that it didnt!) that robbery, rape etc are a large slice of total crime. I also favour simplicity and transparency in stats, especially those intended for the general public – we all know what a crime is, but once you start talking about indexes people start to blank or worse, suspect some sort of manipulation of the data. So I guess my question’d be: what is the problem to which this is the solution? What mistakes are being made because we have the existing stats?

As I understand it, the problem to which this is the solution is that a Crime Harm Index ensures that resources are allocated where they are needed. A number of forces are already using this approach.

You might be interested to read the full article (link in the blog post) for a more thorough rationale.

Thanks for your comment