This is the seventh in a weekly blog series based on the findings of the 2015 annual European Drugs Report published by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. In it, I explore new models being trialled for the legal supply of cannabis.

Models for the legal supply of cannabis

The international legal framework on drug control is provided by three United Nations Conventions which instruct countries to limit drug supply and use to medical and scientific purposes. However, recently these Conventions have been tested, mainly by countries looking to legalise cannabis.

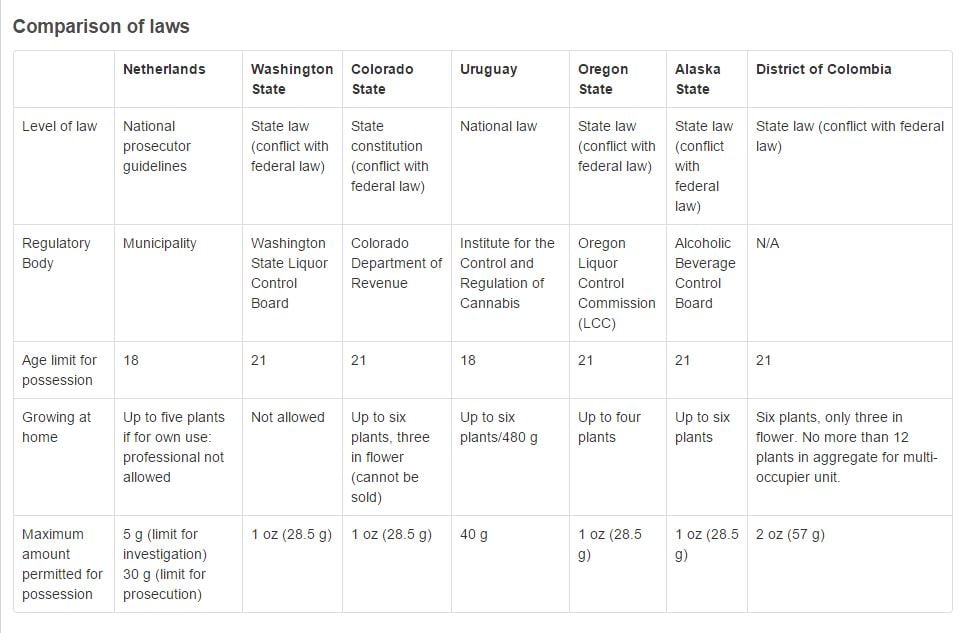

US citizens can buy cannabis legally for medical purposes in 24 states and for recreational purposes in five (Alaska, Colorado, District of Columbia, Oregon and Washington). Intriguingly, these statewide systems are in direct contravention of US federal law where both possession and supply of cannabis are criminal offences. Uruguay has also allowed the legal sale of cannabis. But in Europe, only the Netherlands has sanctioned any form of licensed sale of cannabis.

The details of laws in these different countries are set out in the table below:

[divider]

The Dutch model

In the Netherlands, cultivation, supply and possession of cannabis are criminal offences, punishable with sentences including prison. However, a practice of tolerance, first set out in local guidelines in 1979, has evolved into the present-day concept of ‘coffee shops’, cannabis sales outlets licensed by the council. About two-thirds of councils don’t allow coffee shops, and the number of coffee shops across Holland has fallen from 846 in 1999 to 614 in 2013. The sale of small quantities of cannabis to over-18s in coffee shops is tolerated in an attempt to keep adults who experiment with cannabis away from other, more dangerous, drugs.

A scheme to convert coffee shops into closed clubs with registered members was trialled and then dropped in 2012, but from January 2013, coffee shops were restricted to Dutch nationals only, to be proven by identity card or residence permit. Nevertheless, implementation and enforcement of this rule varies from council to council.

[divider]

Cannabis social clubs

Cannabis social clubs operate on the principle that, if one person won’t be prosecuted for cultivating one cannabis plant in private for his or her own use, then 20 people shouldn’t be prosecuted for cultivating 20 plants together in private for their own use. Clearly this concept is not without its legal difficulties. Establishing what constitutes ‘shared’ production, for example, is problematic and there is the general issue of how activities can be legally distinguished from supply offences. Across the EU, drug supply offences themselves have varying legal definitions but usually require the passing of drugs between persons and some quantity criteria may also apply.

In response, cannabis social clubs have tried to establish operating rules in order to avoid charges of trafficking, drug supply or encouraging drug use. Typical rules are that there should be a register of members, that costs are calculated to reflect expected individual consumption and that the amount produced per person is limited and intended for immediate consumption. Clubs should be closed to the public and new members should be established cannabis users who are accepted only by invitation.

This model, although promoted by activists in Belgium, France, Spain and Germany, is nevertheless not tolerated by national authorities in any European country. This means that cannabis social clubs are likely to be subject to legal sanctions if they are identified.

It is difficult to know how common these cannabis clubs are. The city of Utrecht in the Netherlands announced a project to develop such a club in 2011, but the project has not yet been implemented. Some clubs report that they are operating on a limited basis in parts of Spain, taking advantage of the fact that, although production, supply and personal possession of cannabis in public are prohibited under Spanish law, possession in private spaces is not penalised.

[divider]

Depenalisation, decriminalisation or legalisation?

There are three main terms used in debates about whether countries should make changes to the current situation where, in most states, all drugs are illegal. This EMCDDA video clarifies the meanings of depenalisation, decriminalisation and legalisation, and looks at issues such as regulation:

Conclusion

The legal status of cannabis is starting to feature more frequently in the election campaigns of smaller political parties across Europe and there is a, mainly tacit, acknowledgement on the part of many mainstream parties that the current position of prosecuting cannabis users is out of step with large sections of the electorate.

Many countries are looking to see whether the legalisation of cannabis in some US states (with a number of others holding referenda on the topic) results in increased levels of use and related health problems.

We can expect a lot more discussion of this issue leading up to the next UN General Assembly Special Session on Drugs (UNGASS) scheduled to be held in 2016.