Reduction in heroin supply creates research opportunity

An interesting new (21 January 2016) Home Office report tries to unpick the Impact of the reduction in heroin supply between 2010 and 2011.

The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) reported that a small group of European countries, including the UK, appeared to have experienced a reduced supply of heroin in 2010/11. The Home Office research unit saw this change in the availability of heroin as a unique opportunity to expand the currently limited evidence base on the impacts of reduced supply.

The report examines secondary data to examine how the reduction in heroin supply in England and Wales manifested itself at street level and to attempt to quantify any impact on drug use and associated harms. This data analysis is enriched with feedback from Drug and Alcohol Action Teams (DAATs) and service providers.

The research, by Maryam Ahmad and Anna Richardson, paints an interesting and complex picture.

Key findings

The research drew a number of interesting conclusions on the impact of reduced heroin supply, particularly on drug markets and the drug taking and treatment seeking behaviour of service users.

Drug markets

Typically, the research found that changes in heroin supply varied at a local level with reduced supply occurring at different times and for different durations compared to the overall national level.

There was a lack of availability of heroin reported in many local areas in 2010/11 and a marked fall in the average purity of heroin seizures in November 2010. Although levels generally increased after this, by June 2012 the average purity of heroin seized on the streets did not return to levels previously seen before the reduction in supply.

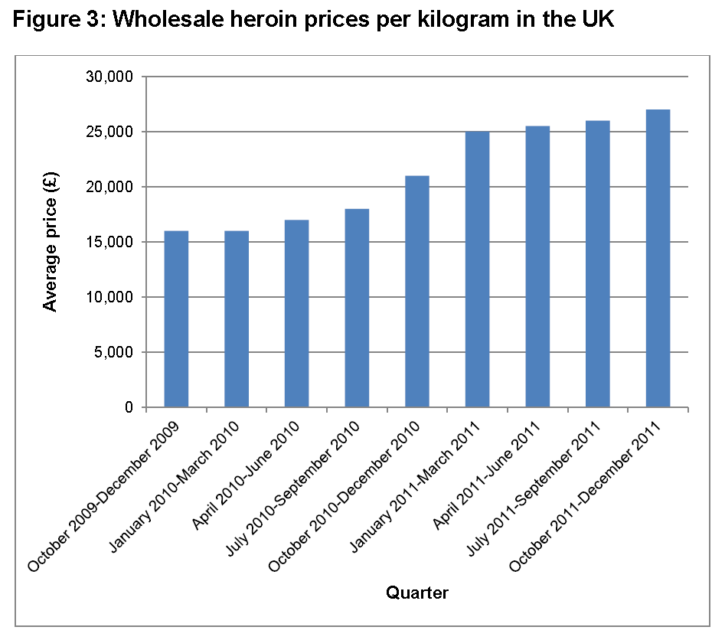

Although wholesale prices of heroin rose substantially (see graphic below), street-level prices remained relatively stable as suppliers chose to reduce purity rather than increase price.

Impact on heroin users

DAATs and service providers reported that many heroin users switched to, or increased their use of, other substances; most commonly benzodiazepines and alcohol.

The evidence on the impact on treatment is contradictory. While the number of new presentations to drug treatment for opiate use in England fell significantly in February 2011 and subsequently did not generally return to previous levels, treatment agencies suggested a more mixed picture. The low heroin purity levels appear to have been a catalyst for some users to tackle their addiction and enter treatment. There were also reports of users substituting heroin for other drugs.

There were no significant falls in England in the number of fatal and non-fatal overdoses shown in the quantitative data during the reported period of reduction in heroin supply period. However, some DAATs did report increases in overdoses in their areas, as well as other side effects, due to the additional adulterants contained in the heroin and/or replacement substances which individuals were using.

Unsurprisingly, no changes were reported in the level of drug-related acquisitive crime committed in England and Wales indicating that heroin users are no more likely to offend or, for those who do not offend, to commit further crime during the reduction in supply. Large numbers of dependent users would need to seek treatment as a response to reduced heroin supply for this to happen. However, there was a significant decline in the number of ‘possession’ as well as ‘possession with intent to supply’ offences for heroin, which the researchers speculate may be due to individuals being less likely to be caught with the drug when there is a lack of heroin availability/reduced purity.

Recommendation

Service providers reported that they increased communication with drug users, colleagues and other services over the period to share information and provide guidance. They recommended that a more reactive and responsive approach should be taken to any future recurrences of a change in drug supply.