Cassia Rowland from the Institute for Government sums up their new Public Services Performance Tracker on criminal courts.

Prison performance

Each year, the Institute for Government’s Public Services Performance Tracker takes a data-driven look at the state of nine key public services, examining spending, staffing, demand, productivity and performance. The criminal justice chapters cover the police, criminal courts and prisons. Over the last two weeks, I’ve summarised the key findings on the police and criminal courts. This week, I turn to prisons.

Per prisoner spending is now back at 2009/10 levels – but this may not last

Day-to-day spending on prisons fell substantially in the early 2010s, but has been rising since 2015/16 and recently crept above 2009/10 levels in real terms. Per prisoner spending has also returned to 2009/10 levels and is expected to rise further until 2026/27. After that point, however, we expect prison spending to fall sharply as Ministry of Justice spending is reprioritised to courts and probation, as implied in the 2025 spending review.

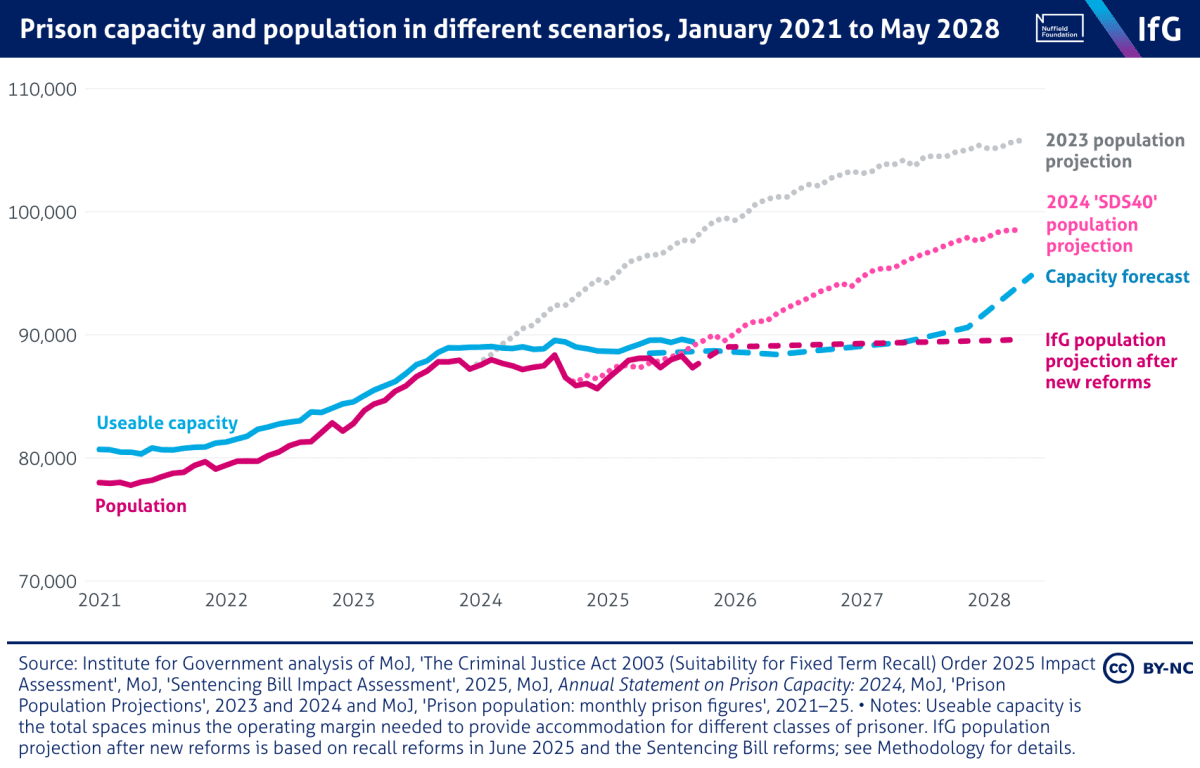

Emergency releases have averted disaster, but capacity will remain on a knife edge until at least 2028

The government managed to successfully stave off disaster through the implementation of various emergency measures to free up spaces in prisons. The biggest of these was ‘SDS40’, introduced from September last year, which saw most prisoners eligible to be released after serving 40% of their sentence in custody, rather than 50%. But by March 2025, the prison population was back at near-record levels. SDS40 bought the government just 6 months. As a result, they introduced further emergency measures, including restrictions to recall, which came into effect in June 2025.

These measures have been enough to keep prisons functioning. But they are still under immense pressure, with adult men’s prisons operating at 97.7% capacity as of the end of September. The government’s Sentencing Bill is intended to get the prison population under control. But even if the reforms save as many places as the government thinks, and all the proposed capacity expansions are delivered on time, demand is projected to outstrip available spaces until at least late 2027. So far, the government has been managing this by preventing spaces being taken out of use for repairs or fire safety work – but this may backfire if cells later become totally unusable.

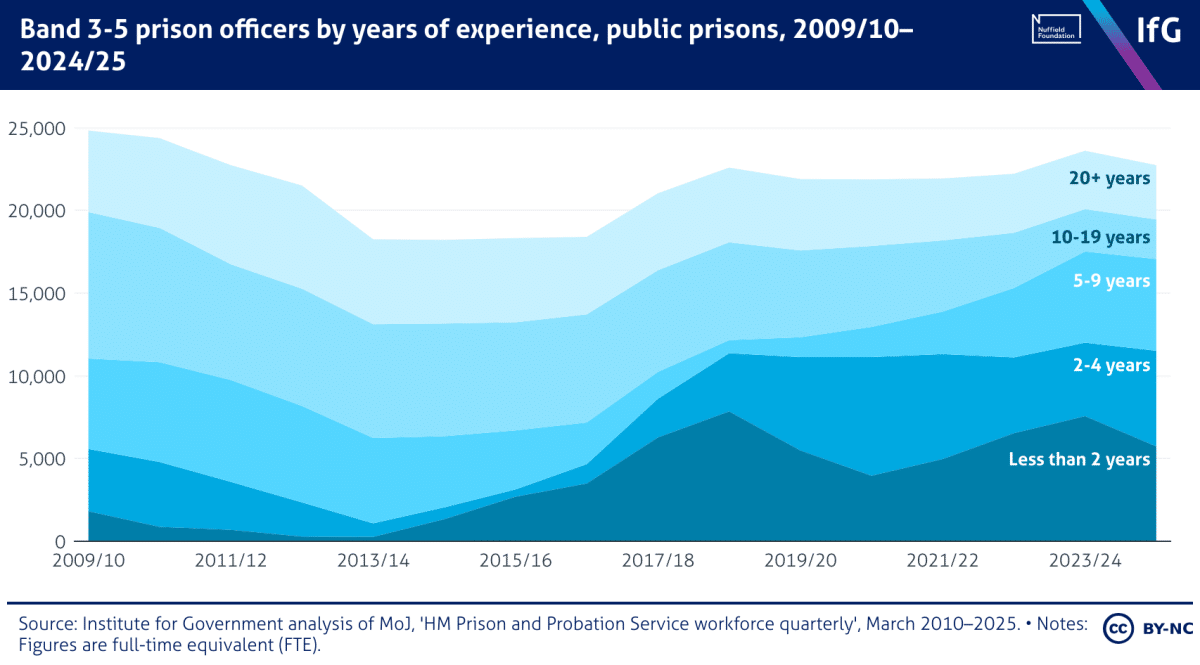

Staff are inexperienced, with a big decline in senior officers, while leaving rates remain high

Prison staff numbers have grown in recent years, but there are still 7% fewer operational staff per 1,000 prisoners than in 2009/10.* There has been a particularly sharp decline for senior officers, down 25% since 2009/10. This is crucial because prisons with more senior officers tend to have lower rates of violence. And recent growth may be being reversed: a drop in officer numbers in the last year has left almost a fifth of public prisons at least 10% understaffed.

Officers are also much less experienced on average, with half of officers having less than five years’ experience. Unlike in policing, this isn’t just because of a hiring surge: it has been consistently true for years. The leaving rate for operational staff in 2024/25 was 12%, more than four times what it was in 2009/10, despite having fallen slightly from its pandemic peaks. Most concerningly, the leaving rate for senior officers has also more than doubled, from 3% to 7%, and shows no signs of falling.

*This section just covers public prisons, as we don’t have workforce data for private prisons.

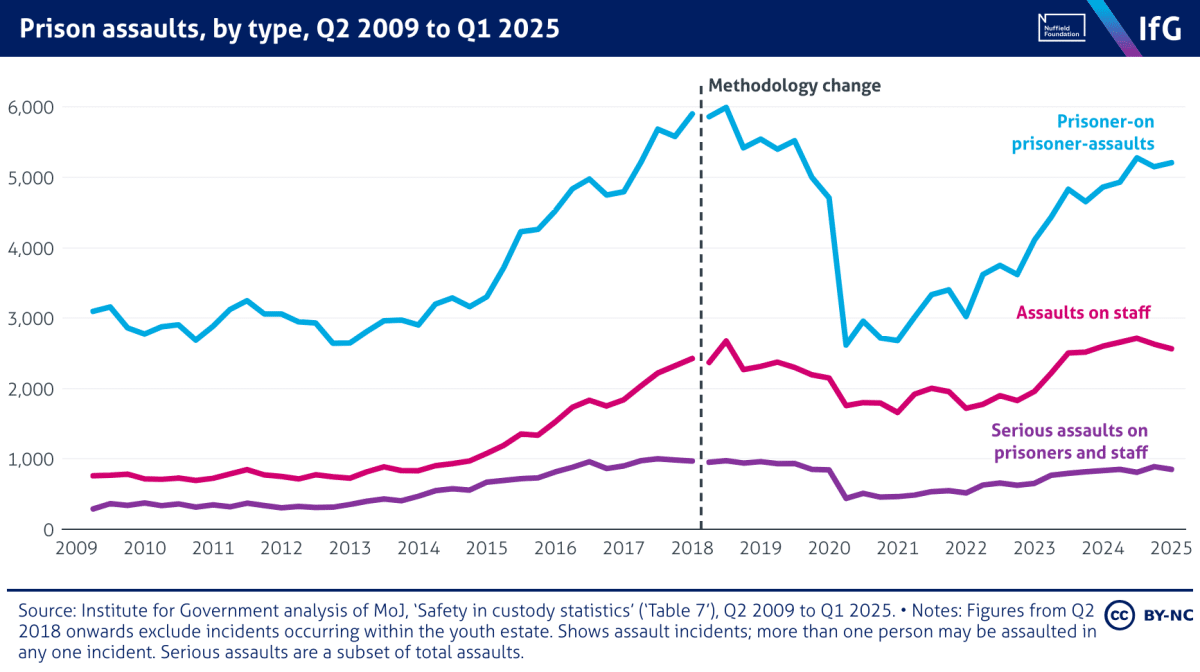

Conditions in prisons are appalling and violence, deaths, self-harm and protests have all shot up in recent years

In 2024, there were more than 30,000 assault incidents in prisons, the second-highest figure on record. More than 10,000 were assaults on staff, up 15% on the year before and the highest ever recorded. Self-harm, protests and deaths in custody all show similarly distressing trends, particularly in women’s prisons, where there are now on average six self-harm incidents reported per prisoner each year. Drug use has become endemic, with around a tenth of men and a fifth of women saying they developed a problem with drugs or alcohol while in prison.

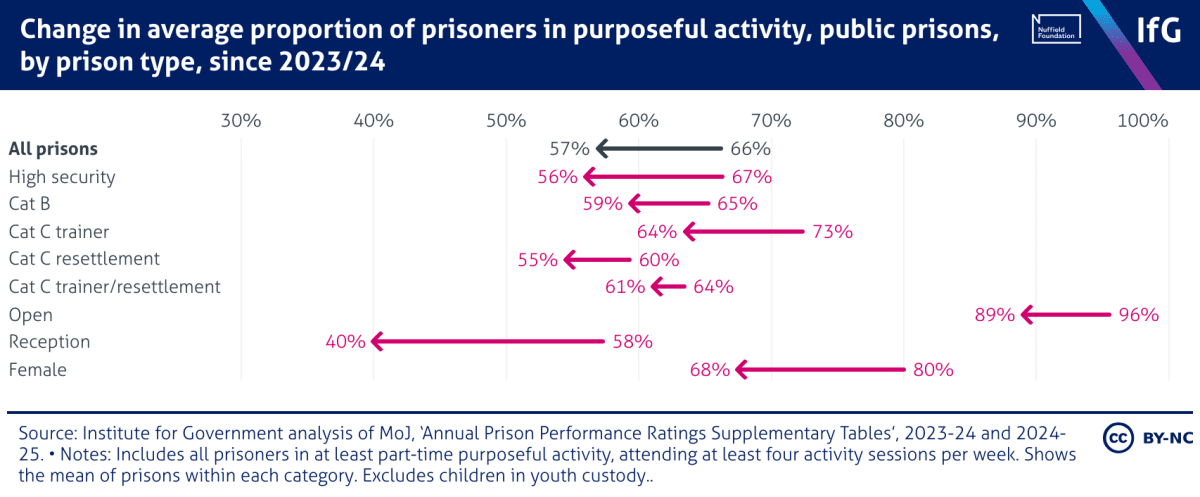

Prisoners are still spending almost all their time locked in their cells, with very limited education, employment or rehabilitative work

There have been further sharp declines in prisoners taking part in ‘purposeful activity’ – training, education, employment or rehabilitative courses. In 2023/24, the median prison had two-thirds of prisoners in at least part-time purposeful activity (four sessions a week). In 2024/25, this fell to 57%. Reception prisons, which hold prisoners on remand or serving short sentences, are by far the worst, but all prison categories have seen drops. More than two-thirds of prisoners spent less than six hours out of their cell on an average weekday, while a quarter were unlocked for less than two.

This lack of activity is almost certainly contributing to high rates of violence, protest and drug use. It leaves prisoners bored with little to do and limited opportunities to earn money, which can increase frustration and fuel the drug economy.

The reforms in the government’s Sentencing Bill will prove hard to implement

In this context it is likely to be almost impossible to implement a true ‘earned progression’ model, as proposed by David Gauke in his sentencing review and set out in the government’s Sentencing Bill. This approach will allow most prisoners to be released after serving a third of their sentence in custody, in return for good behaviour, followed by another third under strict probation conditions and a final third with minimal supervision.

But doing this in a way that actually incentivises improved behaviour is unlikely to be possible any time soon. Lack of access to activity would make it both unfair and unworkable to link release to engagement in work or training, and the urgent need to reduce the prison population means the bar to not be released after a third of their sentence will need to be high. Enforcement of prison rules is widely perceived to be inconsistent and unfair, so tying this to release is likely to inflame tensions between prisoners and officers even further.

Ultimately, improving performance in prisons has to start with easing some of the pressure on capacity so prisons can get the basics right. Only then will it be feasible to focus on improving behaviour and rehabilitation.

Public Services Performance Tracker has been funded by the Nuffield Foundation, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Foundation.

Thanks to Andy Aitchison for kind permission to use the header image in this post. You can see Andy’s work here