A criminal justice system fit for the 21st century

This is a guest post by Sarah Kincaid, Head of Strategy and Insight at Crest Advisory.

Twenty five years ago Tony Blair announced the new Labour criminal justice policy: ‘tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime’. It was a classic piece of triangulation that included the competing punitive and liberal approaches to dealing with crime and offenders that have long characterised criminal justice reform.

Quarter of a century later, despite a plethora of reforms and changes to the justice system by successive governments, the system is arguably neither ‘tough on crime’ nor on its ‘causes’. That is the conclusion of the first part of a Crest research project funded by the Hadley Trust looking at our current system of punishment and rehabilitation, analysing each component of the system and the extent to which it meets its objectives.

The challenges facing justice

Our justice system is facing very different challenges to twenty five years ago. Crime is more harmful, offenders are more prolific and there is less money available.

But unlike other public services, the justice system has failed to adapt. Many of the assumptions underpinning how justice is delivered have remained unchanged. Despite decades of change, there is too little punishment in the community and too little rehabilitation in prison. Failures remain at every stage of the system:

- Low level offending is tolerated, rather than challenged

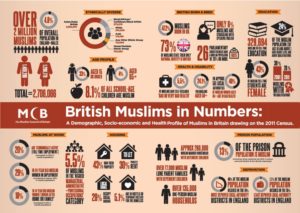

- Punishment within the community is virtually non-existent – meaning prisons are over-utilised

- Prisons and probation are over-stretched and lack the levers to address the social causes of crime, meaning rehabilitation is neglected

Prison

Nothing epitomises the centralising monolith more than prison. It remains the only ‘real punishment’ in the public’s eyes. All other initiatives are built around the presumption that they are ‘alternatives’ to custody, which will always be there as a last resort if things go wrong. Prisons are incredibly expensive to run and manage, they suck up criminal justice resources and in doing so prevent experimentation elsewhere. Increasingly dangerous places to be held, there is little suggestion they are able to tackle the kinds of complex problems that are held within their walls.

The limitations of national policy reforms

The major reforms of the last twenty five years – from the creation of the National Offender Management Service (NOMS) to ‘Transforming Rehabilitation’ – have relied on outdated ‘new public management’ principles of top-down targets and market incentives.

Such approaches were arguably suitable for transactional services (such as refuse collection or hip operations) responding to relatively ‘tame’ problems, which could be dealt with within functional silos, where providers and users respond rationally to incentives. But they are insufficient to deal with the growing complexity of managing offenders, who are increasingly harmful, prolific and chaotic.

Traditional models of reform

| Bureaucracy | Markets | Why this fails the CJS | |

| Theory of change | Outcomes best achieved by rolling out technocratic plans from top down | Outcomes achieved through greater choice and contestability | Outcomes cannot be directly planned for; reoffending has multiple, non-linear causes |

| Methods | Behaviour incentivised by top-down performance targets; services are delivered ‘to’ users | Services are contracted out to external providers; interaction with users is transactional | Systems that are silo’d and centrally managed are not able to manage complexity; services prioritise processes over relationships |

| Suitable problems | ‘Tame’ problems, where we know what works and the challenge is to scale up/ transfer e.g. hip operations | ‘Tame’ problems where providers and consumers respond to market incentives e.g. refuse collection | ‘Complex’ problems where no standard strategy or market incentive can be relied upon to achieve an outcome |

As a result, the criminal justice system does not operate as a 21st century public service. Processes are prioritised over relationships; offenders are treated as homogeneous, rather than a diverse group of people with complex needs. Innovation is neglected at the expense of off-the-peg solutions and the system remains isolated from other public services, which are better able to address the root cause of crime and offending (through access to health, training, housing and skills).

The need for a new model

For years, the UK has been stuck in a stale debate between those in favour of a more liberal/ welfare-oriented justice system (focused on rehabilitation) and those in favour of a more punitive approach (emphasising punishment). This is a false choice. The solution is not to prioritise punishment and/ or rehabilitation over the other – but to combine both.

And we need to look to other systems that are transforming themselves to deal with modern challenges. For example, the new NHS alternative care systems or ‘vanguards’ are aiming to reconfigure the system, reducing the reliance on hospitals (which absorb both budgets and talent) in order to integrate services around the needs of individuals with complex and changing health needs, who drive much of the demand.

We need a new model for the justice system, one which balances punishment and rehabilitation, and which is underpinned by three core principles:

- Devolving power to shift money money upstream, so we can address the root causes of crime and strengthen punishments in the community

- Integrating services around the lives of those who use the justice system, rather than according to Whitehall silos treating offenders as a homogenous group

- Deepening relationships with professionals given the resources and incentives to genuinely transform lives, rather than simply processing people through the system

Conclusion

In the coming months we will be testing practical ideas for change and the principles underpinning them with practitioners, providers and users. In particular we are interested in how prolific offenders – who continue to drive much of the demand across the criminal justice system – could be dealt with in a different way. We are keen to hear your views so please do get in touch if you have insights to share. And keep an eye out for the final report on this project in the summer.

The report can be downloaded here.

One Response

This is more snake oil garbage.