Rona Epstein

Research Fellow at Coventry Law School.

What is hate crime?

The term ‘hate crime’ can be used to describe a range of criminal behaviour where the perpetrator is motivated by hostility or demonstrates hostility towards the victim’s disability, race, religion, sexual orientation or transgender identity.

These aspects of a person’s identity are known as ‘protected characteristics’. A hate crime can include verbal abuse, intimidation, threats, harassment, assault and bullying, as well as damage to property. These strands are covered by legislation which allows prosecutors to apply for uplift in sentence for those convicted of a hate crime.

The police and the CPS use this definition for identifying and flagging hate crimes:

‘Any criminal offence which is perceived by the victim or any other person, to be motivated by hostility or prejudice, based on a person’s disability or perceived disability; race or perceived race; or religion or perceived religion; or sexual orientation or perceived sexual orientation or transgender identity or perceived transgender identity.’

Within England and Wales the police officially monitor five strands of hate crime motivated by a prejudice towards individuals’ presumed race or ethnicity; religion; sexual orientation; disability; and transgender identity. The most recent police statistics reveal that there were 80,393 hate-motivated offences recorded by the police in 2016/2017 – a 29% increase from the previous figures in 2015/2016 and a figure that nearly doubles the recorded figure of 42,255 in 2012/2013. O’Neill, A. (2017) Hate Crime, England and Wales, 2016/2017

Research

The Sussex Hate Crime Project published its report earlier this year; its key findings were:

- Respondents were likely to have been victimised in a hate crime/incident in the past 3 years

- 72% of LGB&T respondents and 71% of Muslim respondents had been victims

- Respondents were likely to know someone else who had been victimised in a hate crime/incident in the past 3 years

- 87% of LGB&T respondents and 83% of Muslim respondents knew another victim

- Experiences of hate crime via the media and online were also extremely common

- 83% of LGB&T respondents and 86% of Muslim respondents had been directly targeted online

- Hate crimes, whether experienced directly, indirectly, through the media, in person or online were consistently linked to Increased feelings of vulnerability, anxiety, anger, and sometimes shame.

- 61% of LGB&T and Muslim participants preferred restorative justice (RJ) as a criminal justice response to hate crimes rather than an enhanced prison sentence. LGB&T participants perceived RJ to be more beneficial to the victim and the offender and were more satisfied with RJ compared to an enhanced sentence.

Too many people sent to prison

In the past 30 years the prison population in our country has risen by 82%. England and Wales has the highest imprisonment rate in western Europe: 145 per 100,000 population. France has 101; Italy – 86; Germany – 76; Norway – 74; Holland – 61. (International Centre for Prison Studies ).

Recently released figures reveal that one in four women – and one in six men – jailed in 2016 were imprisoned for under one month. The figures also show that 36% of prisoners were sentenced to less than three months, a proportion rising to 55% of women. (The Independent, Rob Merrick, 27 December 2017)

We overuse imprisonment for petty crime, and impose short custodial sentences for minor and non-violent offences. ‘Scottish and English data suggest that community sentences are more effective in reducing recidivism than short-term prison sentences (less than 12 months)’. (What Works to Reduce Reoffending: A Summary of the Evidence Justice Analytical Services Scottish Government.

Instead of making efforts to tackle deprivation and social inequality, unmet mental health needs and inadequate facilities to treat alcohol and drug addiction, poor education, lack of decent housing and limited life chances for many in socially deprived areas, we are misusing the criminal justice system to cover the cracks. It’s a punitive approach which leads to a dead end, and a shocking waste of public resources. Those on remand or guilty of minor offences should not be clogging up our prisons which are facing the serious problems revealed in one prison inspection after another. Imprisonment should be used sparingly, and only for serious and violent crime.

We should drastically reduce the numbers of people sent to prison.

Restorative Justice

What about Restorative Justice as an alternative to imprisonment?

I have been reflecting on RJ since reading about the prison sentences imposed on the leaders of ‘Britain First’ earlier this year for a series of hate crimes against Muslims. The group’s leader, Paul Golding, was sentenced to 18 weeks in prison, while deputy, Jayda Fransen, was sentenced to 36 weeks.

My view is this: what a useless destructive sentence to send them to prison – they will surely come out even more hate-filled and bitter than they were when they went in, may wish to appear as martyrs, and may use the prison as a place to spread their poison. What if the court used RJ instead?

What could Fransen and Golding do under a court order instead of sitting in a prison cell? Could they work with groups in our Muslim communities – in education? In childcare? Could they help run a football or other sports, or theatre, or music after school club? Or work with youth workers to get children from a 90% Muslim intake school together with those from a nearby 90% non-Muslim school, getting the children to do art and science and music projects together? Work with people who care for the very elderly? Isn’t there something they could do which would give them an experience of respecting and learning from those in the groups they are currently targeting for senseless, horrible and illegal abuse?

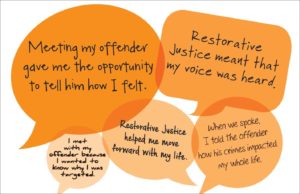

Such an approach requires great skill and intense efforts in working with victims of hate crime – many, perhaps most, victims, would refuse to meet with those who attack and terrify them, entirely understandably. But those who work in RJ find that some victims are prepared to meet perpetrators, and attitudes can change.

The RJ organization Why Me? reports that hate crime victims more often feel traumatised by the incident, with 92% emotionally affected, compared to 81% for victims of crime generally. They are also less likely to be satisfied by the police handling of the incident, with only 52% satisfied, compared to 73% for victims of crime generally. Their research shows that hate crime victims are not currently getting the support that they need. The criminal justice system needs new ways of tackling hate crime and meeting those needs.

‘Restorative Justice has the potential to really address the harms caused by Hate Crime. It has the potential to bring the reality of victims’ suffering into focus for Hate Crime offenders. This can break down prejudice and allow offenders to see the humanity in their victim. It also has the potential to allow Hate Crime victims to take back control by telling their story and having their voice heard.’

Drawing on their evidence the authors of the Sussex report believe that RJ is likely to be supported by LGB&T and Muslim communities as a potentially effective response to hate crimes because it is perceived to be better than imprisonment at:

- Repairing the harms caused to the victim and the community

- Empowering the victim and targeted community

- Educating perpetrators about the harms they have caused

- Reducing reoffending

This leads me to ask: what information about restorative justice had been given to the judge who sent Golding and Fransen to prison?

You can contact Rona here.