Improving resettlement support

This is the third in a series of posts exploring the Ministry of Justice’s plans to re-design its Transforming Rehabilitation project. The MoJ says it wants our views on how best to re-design probation and asks 17 key questions in its consultation document, “Strengthening probation, building confidence”.

This week’s post examines three more questions with the aim of highlighting key concerns and, I hope, of promoting positive ideas about how the MoJ can design a better probation service. The question numbers refer to their numbering in the consultation document, so this week’s post starts with question 7.

Please do take issue with me and set out your views and thoughts in the comments section below.

Question 7: How else might we strengthen confidence in community sentences?

This question follows on from Q.6 covered in last week’s post which asked how to improve engagement between courts and CRCs. The MoJ is clear that it wants sentencers to pass more community sentences for two principal reasons:

- They are much cheaper than the alternative – short prison sentences.

- They are much more effective at reducing reoffending.

Crest Advisory, amongst others, have charted the decline in community sentences (which are being used less than at any time in the last 15 years) with sentencer confidence a key issue, exacerbated by the implementation of TR. A survey of magistrates commissioned for the Crest report revealed that over a third of magistrates (37%) are not confident that community sentences are an effective alternative to custody, and two thirds (65%) are not confident that community sentences reduce crime. As one magistrate put it:

“It may be wonderful what is going on but we want to know what’s going on”.

This quote seems to suggest a straightforward reply to the question. CRCs need to showcase the range of programmes available to offenders placed on community sentences and demonstrate their reliability in delivering high quality supervision. The difficulty for CRCs is that they almost no direct contact with sentencers and are reliant on NPS colleagues promoting the range of community sentences in court. It is difficult for NPS staff to speak with authority about interventions delivered by another organisation of which they have no first hand knowledge.

Question 8: How can we ensure that the particular needs and vulnerabilities of different cohorts of offenders are better met by probation? Do you have evidence to support your proposals?

The MoJ consultation paper repeats what we know from the evidence about successful supervision:

Evidence suggests that rehabilitative work is most effective when it is structured and tailored to the offender’s learning style, when the intensity of support and intervention is matched to the offender’s risk of reoffending, and when the causes of their offending are addressed in a coordinated way alongside practical and social needs.

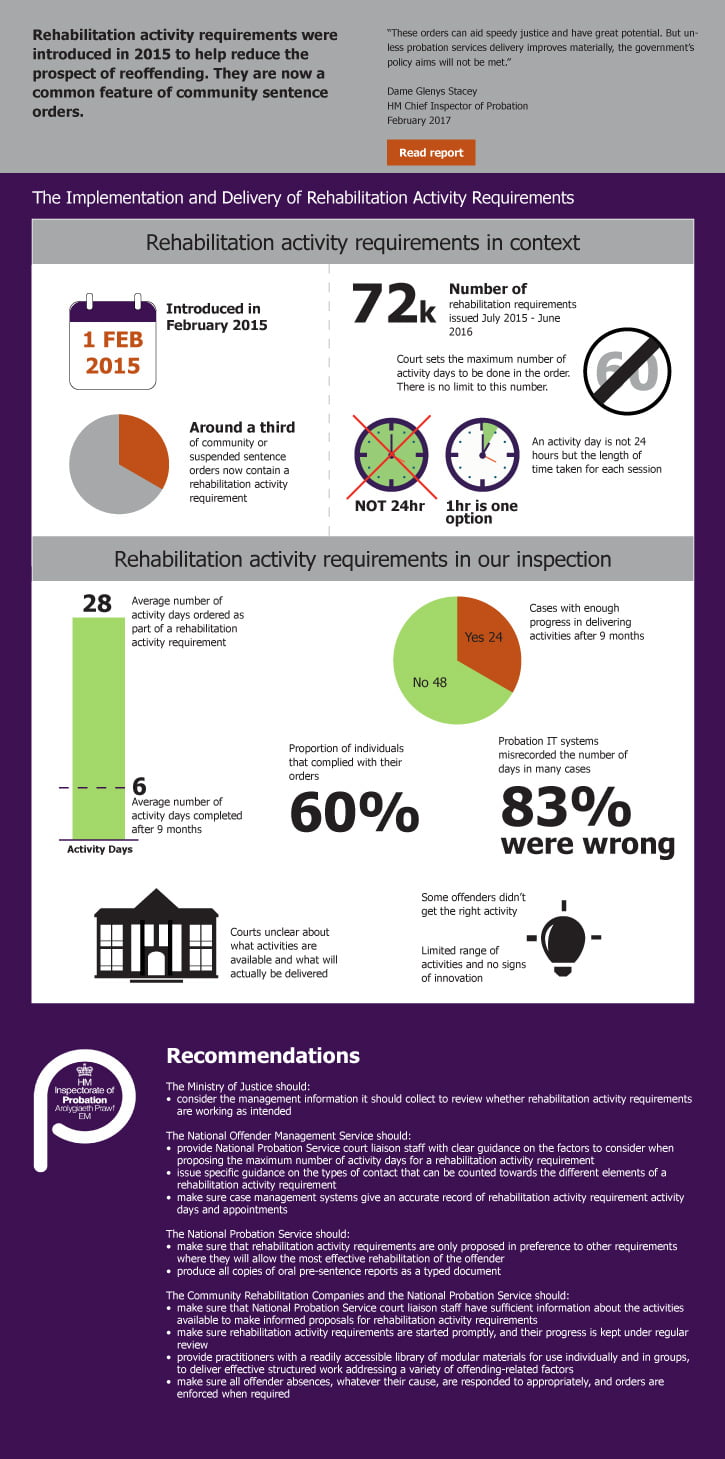

It is clear that Rehabilitation Activity Requirements (RARs) which were introduced in 2015 to allow new probation providers flexibility in how they delivered supervision have generally been of poor quality. The HMI Probation report into them found:

- Although 28 was the average number of activity days ordered by a court as part of a RAR, the average number completed after 9 months was just 6

- Two thirds of cases had not made sufficient progress in delivering activities after 9 months

- Probation IT systems misrecorded the number of days in 83% cases.

You can see the inspectorate’s summary of RAR performance in the infographic below:

The MoJ says in its consultation paper that it wants to “strike the right balance between ensuring consistent availability of interventions to address the key needs linked to reoffending and giving providers the flexibility to decide how they will secure improved outcomes.” It declares an intention to will define more clearly what can be delivered as part of a RAR and will ask providers to develop low, medium and high intensity RAR services for which it will develop new output and outcome measures.

The MoJ identifies a number of groups which require specialist probation provision:

These include female offenders – many of whom will often present a range of complex needs – black and minority ethnic (BAME) offenders, and those with learning disabilities, autistic spectrum disorders, and mental health and substance misuse problems.

The department also gives a low-level endorsement of the need to involve more voluntary sector organisations in delivering specialist interventions.

Surely, it is the return of this voluntary sector expertise which is critical to restore the quality of service to the groups listed above?

Question 9: How could future resettlement services better meets the needs of offenders serving short custodial sentences?

TR was originally sold on the basis of improving resettlement for short term prisoners and the complete failure of CRCs to provide resettlement support to this group has been one of the most damning and persistent criticisms of the programme. To repeat the probation inspectors verdict reproduced in last week’s post:

Support for prisoners leaving jail and moving back into the community was poor and the work of most Community Rehabilitation Companies (CRCs) was not making any difference.

In the consultation paper, the MoJ accepts that one of the main reasons for this was that the department did not resource this provision properly and announced that it is investing an additional £22m per year for 2019 and 2020 for CRCs to deliver “an enhanced level of through-the-gate support”.

The MoJ also sets out how it expects its new model of offender management in custody (OMiC) to improve pre-release support. OMiC is designed to align offender management roles and tasks across prison and the community, and remove duplication and confusion. Prisoners with more than 10 months left to serve will be allocated to a prison-based offender manager who will provide supervision and support during the prison part of the sentence, while those with less than 10 months to serve will be allocated to an offender manager in the community. The new approach is intended to ensure there is a more effective handover of responsibility between offender managers in prison and the community.

In addition to improving pre-release preparation and resourcing post-release support properly, the MoJ needs to lobby the Treasury and other government departments to reverse some of the many cuts in community provision. However, perfect the new CRC providers are, they will not be able to develop more housing for released prisoners, 30% of whom were released to unsettled or unknown accommodation in in 2016/17.

3 Responses

Commenting on Q8: my particular focus is on offenders who may have learning (intellectual) disabilities. I am very concerned to hear anecdotal evidence that the pressure on courts to deliver ‘speedy’ justice is restricting the possibility that probation and/or liaison and diversion services may be allowed the time to assess a defendant properly and advise the court about both reasonable adjustments to the process and sentencing options. People with ‘invisible’ disabilities such as learning disabilities or autism may be particularly disadvantaged. This seems to me to show a real clash between MoJ/HMCTS policies on the one hand and equalities and human rights laws on the other. Further, I hear from a court perspective that community sentencing options for offenders with learning disabilities are not well developed in most areas and it can be difficult for the court to feel confidence in a community sentence. Supervision for an offender with learning disabilities may need to be much more intensive (and certainly face to face), and the supervisor needs to be confident in making reasonable adjustments in their practice (e.g. adjusting their communication style, offering easy read materials, using a digital clock, organising additional support for a person to attend appointments, etc, etc). Community sentences may require close collaboration between probation, public health, social care and health services to ensure the availability of adapted programmes and of the support needed to comply. However, cutbacks in all of public health, social care and health services threaten such collaboration and offenders with mild learning disabilities may well not meet the eligibility criteria for specialist learning disability services (some learning disability teams now set a criterion that they only work with people who have an assessed IQ of 50 or below). Changing this picture requires a joined up approach across the agencies and cannot be resolved by probation alone.

Sorry, I didn’t intend my comment above to be anonymous. I hope I’m correcting this here.

Alison Giraud-Saunders

Thanks Alison. It certainly seems to me that much of the work that many probation trusts were starting (belatedly in some cases) to develop for offenders with learning disabilities has been eroded since the double threat of austerity & TR. I’d be delighted to be corrected by any NPS/CRC staff who feel they are following best practice.