Responding to the MoJ consultation

This is the second in a series of posts exploring the Ministry of Justice’s plans to re-design its Transforming Rehabilitation project. The MoJ says it wants our views on how best to re-design probation and asks 17 key questions in its consultation document, “Strengthening probation, building confidence”.

This week’s post examines three more questions with the aim of highlighting key concerns and, I hope, of promoting positive ideas about how the MoJ can design a better probation service. The question numbers refer to their numbering in the consultation document, so this week’s post starts with question 4.

Please do take issue with me and set out your views and thoughts in the comments section below.

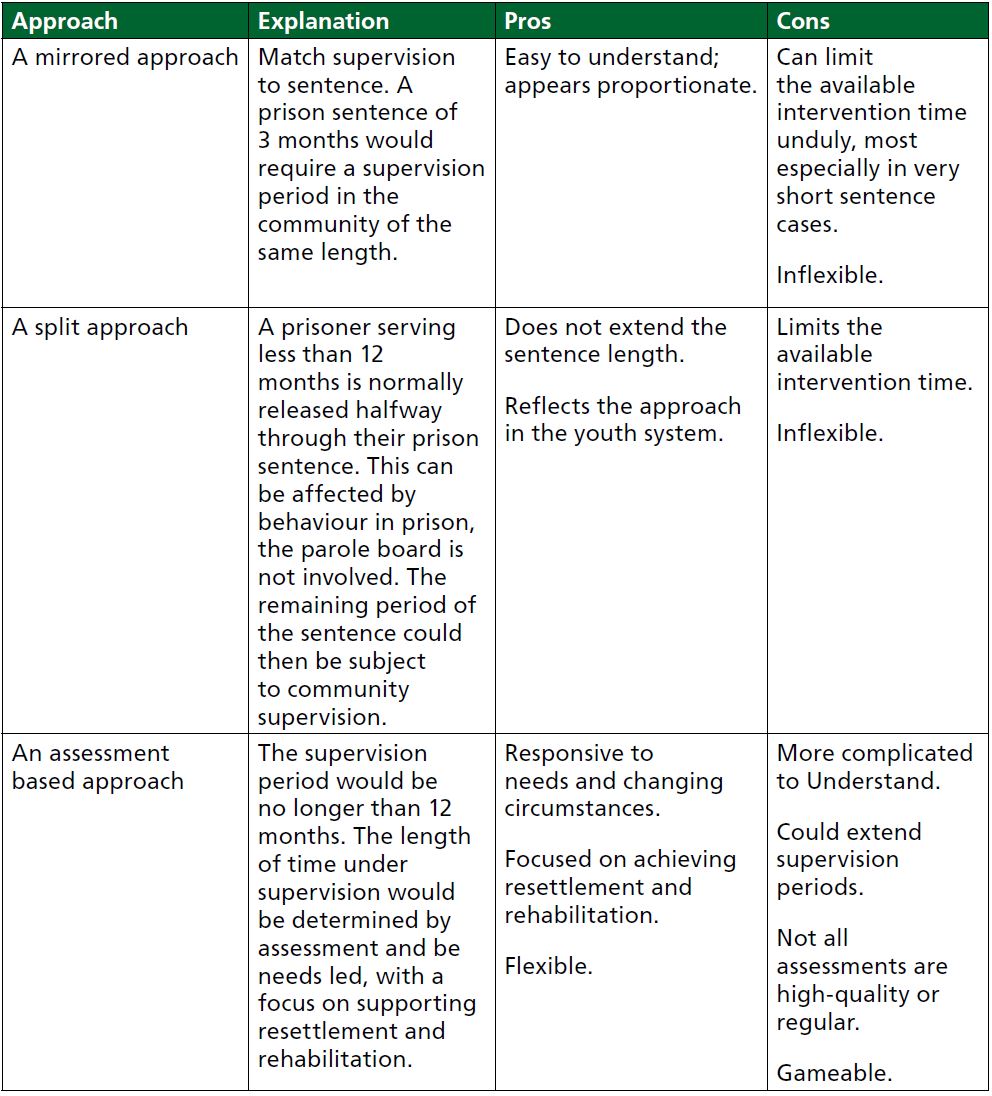

Question 4: What changes should we make to post-sentence supervision arrangements to make them more proportionate and improve rehabilitative outcomes?

As regular readers will know, the Offender Rehabilitation Act 2014 extended supervision on licence to approximately 40,000 offenders each year who are released from custodial sentences of less than 12 months. No-one argued with the need to provide support and supervision to this group of people who have the highest reoffending rate (64% in the first year post-release). However, the lack of funding in the CRC contracts has meant that hardly any of the resettlement work, whether in custody or on release, has been done. Here’s the view of the probation inspectors:

Support for prisoners leaving jail and moving back into the community was poor and the work of most Community Rehabilitation Companies (CRCs) was not making any difference.

This lack of resettlement support has been aggravated by the impact of cuts in public services, making it even harder than before for released prisoners to access such critical support as accommodation and help with substance misuse and mental health issues.

the year to December 2017).

For what it’s worth, my view would be an amended version of the Committee’s split approach: post-release support being the second half of the sentence, but with a minimum supervision period of three months to ensure that released prisoners received some form of support.

This, of course, is the more substantive issue; the injustice of post-sentence supervision at the moment is that released prisoners have nothing to gain (they are rarely receiving any proper support) but everything to lose (non-compliance results in recall to prison).

The most important change is for the MoJ to properly resource pre-release planning and post-release support.

Question 5: What further steps could we take to improve the effectiveness of pre-sentence advice and ensure it contains information on probation providers’ services?

The demise of the pre-sentence report and its probable link to the very substantial drop in the number of community sentences is an issue of grave concern to the MoJ. The only real way to square an effective justice system with the demands of austerity is to reduce the prison population and reversing the trend on community sentences is a key component of this.

Sentencers’ loss of confidence in probation and in CRCs in particular appears to be part of the problem; which is, of course, exacerbated by the fact that Magistrates and Judges have almost no contact with CRC personnel; all court work being undertaken by the NPS.

There are practical solutions; developing an app to go on sentencers’ iPads which allows the range of interventions to be described and kept-up-to-date, preferably with real-time performance data. The more permanent solution though, is a cultural one, the NPS and CRC need to think of themselves as parts of the same probation service, rather than separate entities, for the NPS to effectively recommend sentencers to place offenders on CRC-run interventions. That will be hard to achieve within the Justice Secretary’s commitment to a split service.

This issue is integral to the MoJ’s next question:

Question 6: What steps could we take to improve engagement between courts and CRCs?

Again, this is hard to achieve when sentencers routinely have no contact with their local CRC. The MoJ says that they have reinstituted the National Sentencer and Probation Forum to enable magistrates, NPS and CRCs, court staff, prosecutors and others to come together and discuss the challenges and opportunities for improvement. This has led to a new Local Liaison Probation Instruction to ensure that “CRCs play a part in local discussions with courts about probation services, and to work to improve the relevance and reach of the NPS Sentencer Survey and Sentencer Bulletin”.

The reality is that this sort of instruction is likely to make little difference to most sentencers’ knowledge and understanding of local programmes. Again, information on sentencers’ iPads enlivened by case studies and with video testimony from service users, is the best I can recommend. Having up-to-date information when faced with a real-life decision is more helpful than trying to remember what it said in a half-read sentencer bulletin several months ago.

Next week’s questions are equally challenging looking again at improving confidence in community sentences, how to meet the needs and vulnerabilities of different offenders and improving resettlement.

One Response

Its most likely going to look like the current TR, a mess of failure, financial bungs to private companies, more staffing cuts and scaled back service, less charity involvement, no minister responsibility for failure, more awards for civil servants. We will be in the same position in 5-7 years for TR3.