This is a guest post by Roland Karthaus, Director of Matter Architecture, on a report published earlier this week (6 December 2017) on well-being in prison design.

Prison design can influence behaviour

Arguments about the cost and wastefulness of re-offending are well-worn and are central to the current debate about huge challenges facing the penal system in England and Wales. While these challenges have been acknowledged by the government, what hope of improvement? A glimmer of hope can be found in what seems to be the widest consensus for decades that things must change. Despite the shelving of the Prisons and Courts Bill white paper earlier in the year, there remains strong momentum behind the reform agenda and a commitment to the primary objective of rehabilitation.

Standing at just over 86,000 in early December 2018, the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) accommodates the equivalent population to some of the UK’s smaller cities (for example Bath) in buildings ranging in age from brand new to more than a century old. What has so far been largely overlooked is the role that these buildings and the land they occupy do and could play in shaping people’s chances of successful resettlement.

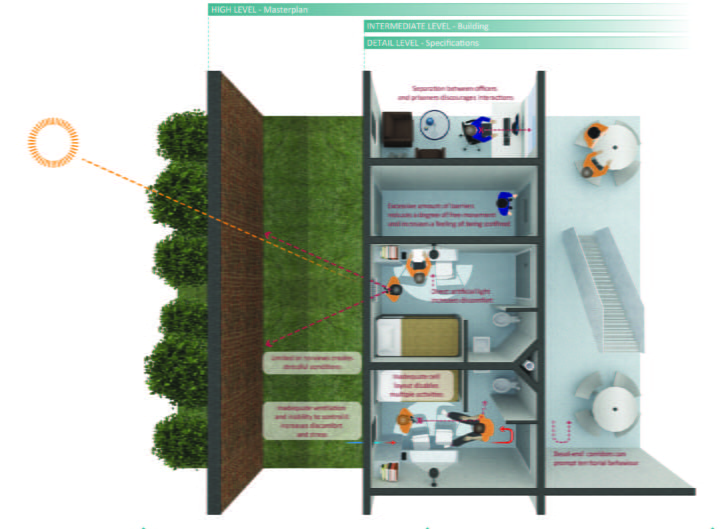

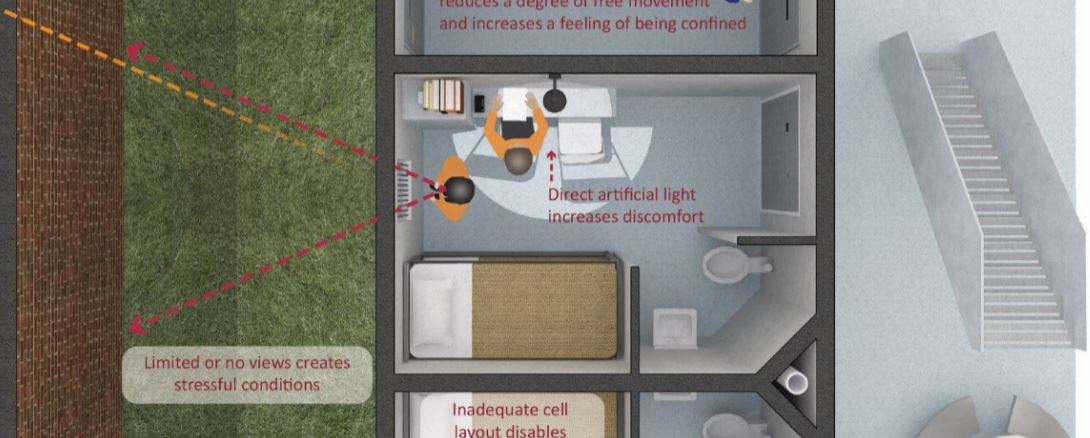

Our built environment does not determine our behaviour, actions or future, but it strongly influences them, as evidenced by decades of sociological studies. Direct cause and effect are hard to prove, but a relatively young field of research: environmental psychology provides a basis for linking specific characteristics of the built environment, such as daylight, noise, views, scale, shapes and colours with long-term health and wellbeing. Environmental psychology is not a ‘pure’ academic field, in that it draws on knowledge and research from diverse disciplines, including anthropology and neuroscience, to theorise and test how humans respond to their environments. These responses are often hard-wired from our evolutionary past and so have a degree of universality, albeit affected by our personal experiences.

Environmental psychology

Past environmental prison studies have tended to focus on behaviour, especially measures to avoid violence, but environmental psychology is focused on health and wellbeing, due to physiological changes, triggered by environmental conditions. This is crucial for rehabilitation in two main ways. First, support and training programmes that are delivered in prison require a certain level of capability that people who are physically or/and mentally unwell struggle to achieve. Second, resettlement form an institutional setting requires a degree of self-efficacy that needs similar levels of well-ness. As those in prison disproportionately suffer from mental and physical ill health to begin with, an environment that exacerbates these is a strong inhibitor of rehabilitation.

As well as being far from the truth in some establishments, arguments about ‘luxurious’ or ‘cushy’ conditions in prisons are not just inaccurate but extremely unhelpful in this respect. I have yet to visit a prison where even major improvements would bring it close to being comfortable, but I have been in many where the degree of discomfort is very likely to be harmful, both for staff and prisoners, even to those who become used to these conditions over time. This is not an intended part of any sentence: the deprivation of liberty is the punishment of prison and such further punishment is evidently self-defeating. What is often forgotten is that conditions are frequently not much better for officers, staff and visitors who deserve no punishment, but whose efficacy and morale are crucial to the success or failure of rehabilitation.

Cost effectiveness

Prison cost very nearly £3 billion last year. Re-offending costs range from £9.5 billion to £13 billion annually according to the ONS. The cost of building the UK’s newest prison, HMP Berwyn with a capacity of 2,106 was around £250 million and will most likely be in use for more than 30 years. If the design of such buildings is holding back the rehabilitation of people accommodated in them and consequently contributing to re-offending, then these costs will significantly outweigh the costs of their construction. In other areas of society, proving this connection has been unnecessary; we have designed enough libraries, schools, hospitals, homes and other buildings that respond to the factors of environmental psychology that our expectations have changed. New buildings are now normally full of light, air, views and colour. Many of these measures have even been formalised in planning and semi-compulsory design guidance. But the special circumstances of prisons require a firmer logic for such improvements to be made.

New report

This week our team published online the report, Wellbeing in Prison Design: a guide, a culmination of a six-month project funded by Innovate UK and the RIBA Research Trust and has benefited from the engagement of the MoJ’s Prison Estate Transformation Programme (PETP), which is commissioning new prisons to replace older existing buildings. The PETP is focused on supporting rehabilitation and our project has developed in parallel with this process, providing a chain of evidence between design measures and the strong likelihood of outcomes.

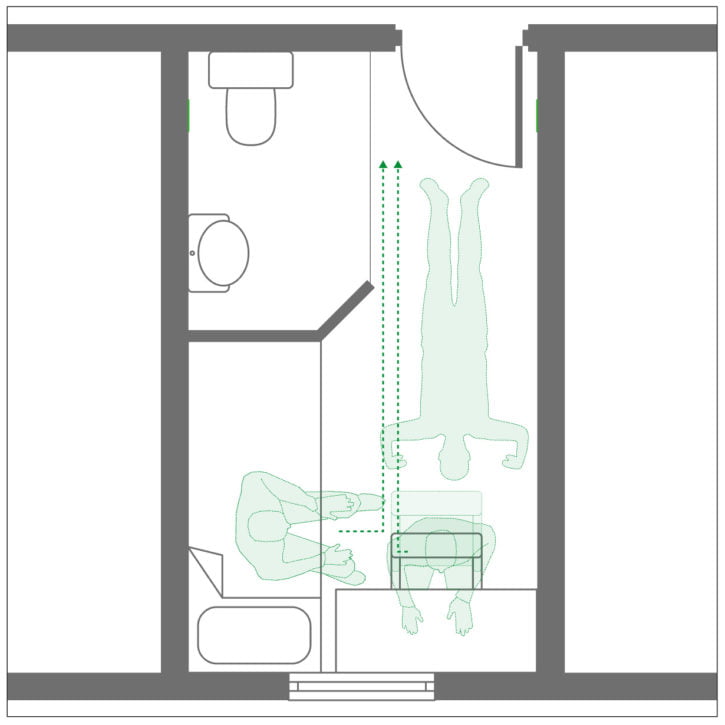

The report is designed to be practical and is broken down into sections that outline the context and the literature-based research and fieldwork in HMP Berwyn that have provided evidence for our findings. Through on-line surveys, we gathered information from staff and men in custody about their on responses to their new environment. These surveys are still being analysed, but they highlight some environmental factors such as noise that most agree are detrimental to their wellbeing. The balance of the report takes the form of a series of design measures, at differing levels of detail, where there is good evidence of positive impact. These are not simple check-box design solutions, but areas that need to be considered as part of a holistic design process.

Meaningful consultation with prisoners and staff

In developing this work and relating it to current and emerging prison design, it is clear to us that the commissioning and design processes themselves need attention to ensure they deliver rehabilitative environments. The degree of consultation and engagement with our research team, with end-users and management teams in prisons being undertaken in the procurement currently underway is admirable and represents a step-change in thinking. To ensure success and longevity, this approach must be systematised and embedded within the wider culture of holistic asset management, operations and procurement, both within the wider MoJ and HM Treasury.

Recommendations

A key recommendation of our report is that a process of independent design review should be established, as is common in other areas. Better financial accounting for longer-term savings resulting from extra expenditure in the design of supportive environments needs to be agreed upon (by which I do not mean PFI). And a discussion needs to be opened about the potential rehabilitation value of the whole MoJ estate, including the land surrounding prisons, as explored in an RSA report published in 2014 to which I contributed.

In times of limited resources, the necessity of understanding how our buildings can generate huge savings through social purpose and value has never been greater. In other areas this understanding has advanced dramatically over the 20 years I’ve been working in architecture, but prisons have a lot of catching up to do.

Roland Karthaus, Director, Matter Architecture. Roland Karthaus co-founded Matter Architecture with Jonathan McDowell in 2016. He has been a registered Architect since 2002, a Member of the Royal Institute of British Architects, an RIBA Client Adviser and a member of the RIBA Planning Group. He is a Fellow of the RSA and a Design Council Built Environment Expert. Matter’s Lucy Block and Anthony Hu worked together with Roland and the University of East London’s Agata Korsak to conduct the work.

2 Responses

Broken link

Tested and working this end, Juan. Presuming you mean the link to the report…

Best Wishes

Russell