The Chromis Programme

Last week (7 May 2020), HMPPS published exporatory research of its Chromis accredited prison programme which aims to reduce violence in adults whose level or combination of psychopathic traits disrupts their ability to engage in treatment and change. At the time of publication Chromis had recently stopped running within HMPPS. However, the approaches of the programme continue to inform the work of the unit where it was delivered and informed the development of subsequent interventions that continue to run across HMPPS.

It is also the case that many Chromis participants are still serving sentences and continue to attract attention as a result of their history and the nature of their offending. As such, research into the effectiveness of Chromis and its approach which has informed their risk reduction work remains relevant for the service.

This study makes use of a multiple case study design to review changes in four areas that are markers for treatment success and important to stakeholders across a purposeful sample of five men who had completed treatment and progressed from the prison unit. These areas are: risk factors targeted by the programme, institutional behaviour, engagement in interventions and regimes and protective factors.

About Chromis

Chromis does not aim to change personality traits but to work with these to reduce individuals’ risk of violent offending. To do this it does not require participants to be motivated to change, however, it necessitates them to be open to learn new skills that will provide them with strategies for self-management.

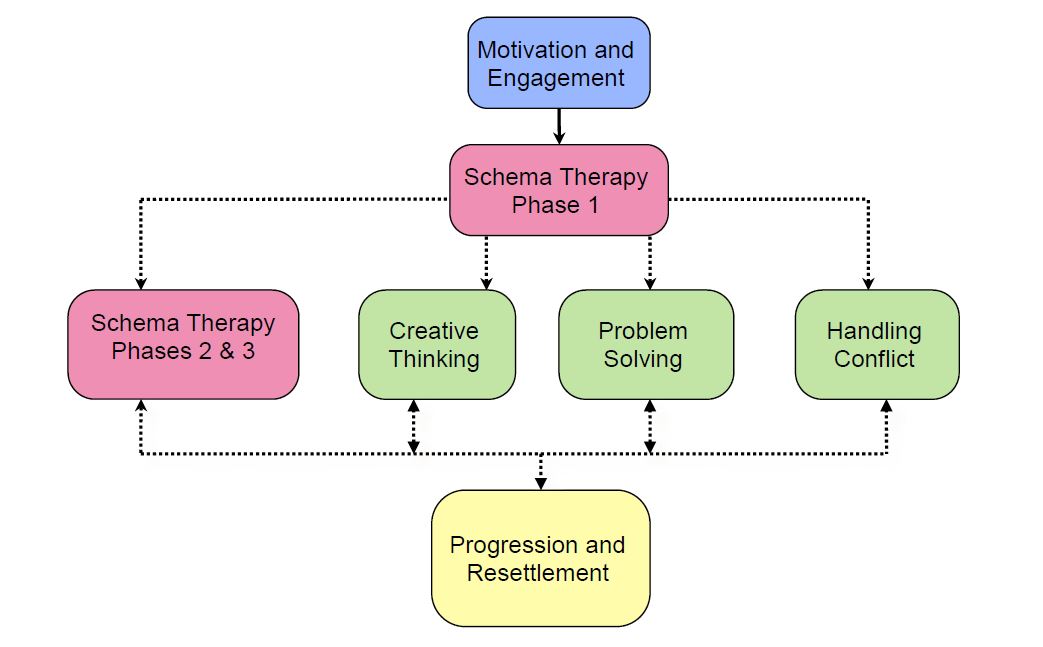

Chromis comprises of five separate components; each with specific treatment targets aimed at addressing the risk and needs of violent men with high levels of psychopathic traits (see graphic below). Chromis initially aims to genuinely motivate and constructively engage participants in treatment rather than emphasising compliance. It does this by identifying what they really care about and by focusing treatment goals on achieving these aims pro-socially.

A formulation is then completed that explores the development and maintenance of unhelpful schema, beliefs and consequent behaviours. This helps to inform which components an individual needs to complete and in which order. There are three cognitive skills components that aim to give participants a chance to learn and develop skills relating to their thinking and interpersonal skills and problem solving. There is also a Schema Therapy component, which is based on cognitive behavioural therapy for personality disorders. This makes use of behavioural experiments in the participants’ life to test out beliefs and practice new skills.

Although the graphic depicts components following a particular order this is not a necessity as they can be sequenced according to individual requirements. Gaps can be taken between the components to allow for consolidation of learning or to attend other interventions. There is also flexibility within components, for example some sessions can be run individually or in small groups depending on individual need. The time taken to complete Chromis therefore depends on individual need and progress, but is likely to be between two and half to three years, including assessment and preparation for progression.

Conclusions

The study found indicative evidence that individuals can and do engage in Chromis. It is also notable that all participants appeared to have gained benefits from completing Chromis, linked but not confined to, the overall aim of reducing violence. Changes in recorded incidents of physical aggression, self-reports of anger, adjudications and changes in violence risk assessment outcomes all pointed towards positive developments in this regard.

From discussions with case study individuals they reported they were better able to delay action; thinking of consequences and considering alternatives. Relating skills to achieving their own goals seemed critical in achieving this. Developments in relationships with staff, particularly uniform staff also seemed important to supporting improved institutional behaviour for individuals.

This research had a number of limitations and further work is needed to build the evidence base for programmes to reduce violence in individuals with high levels of psychopathic traits within prison. While caution needs to be used when extrapolating findings from multiple case study projects to wider groups, this study provides promising findings that may be less apparent from larger scale less individualised approaches.

Thanks to Andy Aitchison for kind permission to use the header image in this post. You can see Andy’s work here.