Anyone and everyone who wants accurate up-to-date information on what is going on in our prisons relies on the prison factfiles produced by the Prison Reform Trust.

Known as the Bromley Briefings, they are issued twice a year. The Winter 2019 issue was published on Monday (27 January 2020).

As well as all the latest penal statistics, each edition has a theme and the current edition opens with a detailed “long view” of how sentencing for the most serious crime has become dramatically more severe over the last two decades. Politicians may well be right that many of their constituents believe that the criminal system has gone “soft on crime”. But the way we exact retribution for the serious sexual and violent crimes that most often grab the headlines is actually much tougher than it has been in living memory. By way of example, for life sentences the guaranteed minimum period in custody has risen from 12.5 years on average in 2003 to 21.3 years in 2016.

For the same crimes people are spending much longer in prison as well as longer under supervision after their release. They also face a much higher likelihood of being recalled to prison after release—around 8,000 people are currently in prison for that reason alone.As usual, I have perused the Briefing in depth and found 10 key facts to share in this post.

Since readers of the blog are more than averagely well informed about penal affairs, I have tried to feature some of the less well-known issues.

1: Long tariffs

By the end of September 2019, there were 3,555 people in prison serving a life sentence with a tariff of between 10 and 20 years. More than one in five (779) were still in prison having already served their tariff. A further 1,872 had tariffs of over 20 years, of whom 48 were beyond their tariff point. 880 people had a tariff of more than 25 years, 291 had a tariff of more than 30 years, 264 had a tariff of more than 32 years, including 63 people were serving the state’s most extreme punishment, a whole life tariff—and are unlikely to ever be released

2: The over-use of prison

In England and Wales, we over-use prison for non-violent and persistent crime. 56,000 people were sent to prison in the year to June 2019; 67% had committed a non-violent offence and almost half (46%) were sentenced to serve six months or less.

3: The recall rate keeps growing

Anyone leaving custody who has served two days or more is now required to serve a minimum of 12 months under supervision in the community. As a result, the number of people recalled back to custody has increased, particularly amongst women. 8,956 people serving a sentence of less than 12 months were recalled to prison in the year to June 2019.

4: Prison safety gets worse

Safety in prisons has deteriorated rapidly during the last seven years. People in prison, prisoners and staff, are less safe than they have been at any other point since records began, with more self-harm and assaults than ever before. The number of self-inflicted deaths has also risen once again. Inspectors found that safety was not good enough in nearly two-thirds of male prisons (63%) they visited last year. More than half of people in all prisons said that they had felt unsafe at some time whilst in prison.

5. Prison resources

HM Prisons and Probation Service (HMPPS) has experienced significant cuts to its budget in recent years. Between 2010–11 and 2014–15 its resource budget was reduced by 20%. Despite recent increases, its resource budget remains 12% lower than in 2010–11. The cost of a prison place reduced by 16% in real terms between 2009–10 and 2018–19. The average annual overall cost of a prison place in England and Wales is now £43,213.

6: Muslim prisoners

The number of Muslim prisoners has more than doubled over the past 17 years. In 2002 there were 5,502 Muslims in prison, by 2019 this had risen to 13,341. They now account for 16% of the prison population, but just 5% of the general population. Muslims in prison are far from being a homogeneous group. Some were born into Muslim families, and others have converted. 40% are Asian, 29% are black, 16% are white and 9% are mixed. Only 169 people, 1% of Muslims in prison, are currently there for terrorism related offences.

7: Indeterminate sentences for public protection (IPPs)

Despite its abolition in 2012, there are 2,315 prisoners in prison serving an IPP sentence who have never been released. More than nine in 10 people are still in prison despite having already served their tariff—the minimum period they must spend in custody and considered necessary to serve as punishment for the offence. 16% of people who have yet to be released have a tariff of less than two years, and 40% have a tariff of between two and four years. 358 people have yet to be released from prison despite being given a tariff of less than two years — over half of these (187 people) have served ten years or more beyond their original tariff. There are a further 1,206 people serving an IPP sentence who are back in prison having previously been released—a 25% rise in only a year. The Parole Board has said it remains concerned about this.

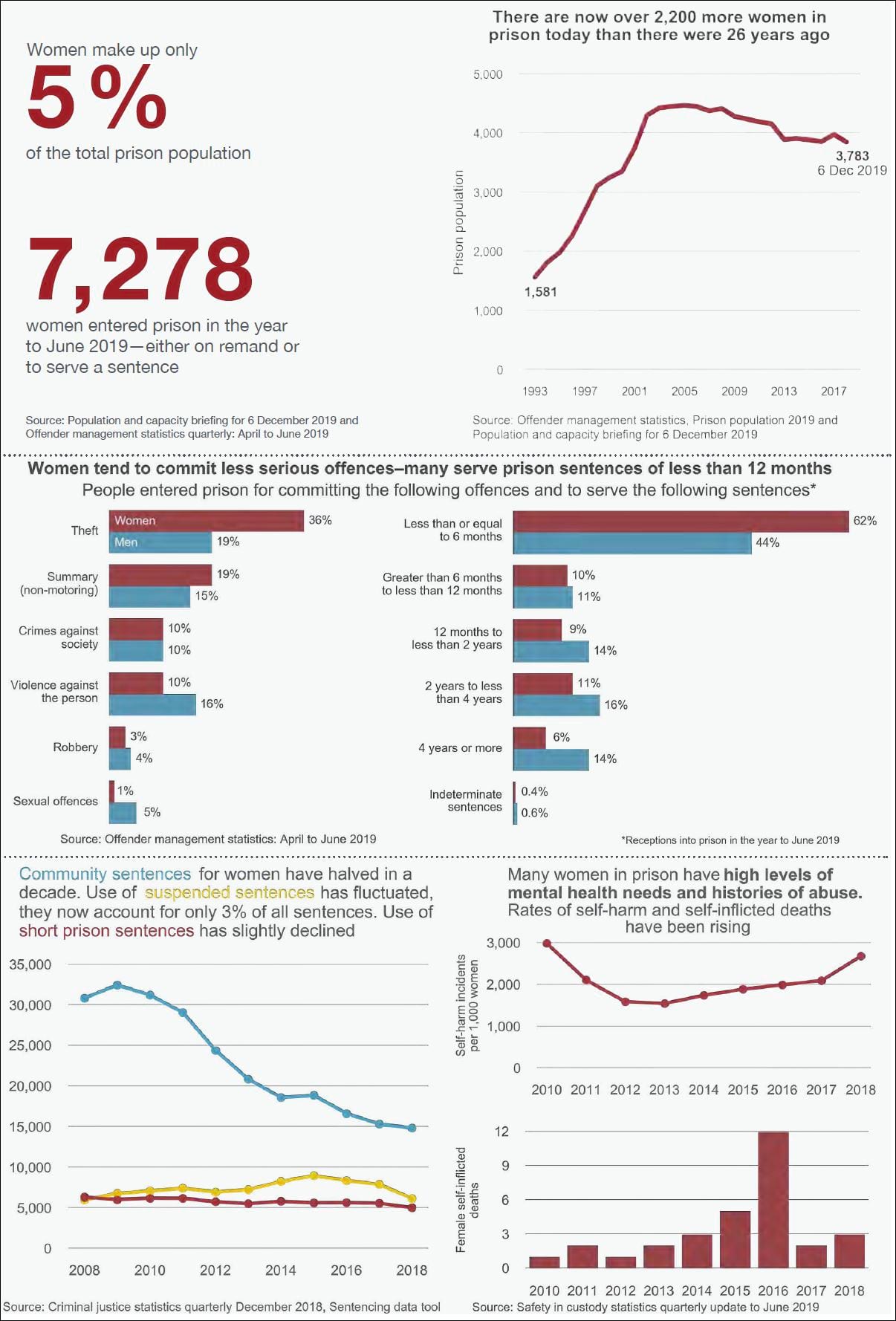

8: Women in prison

On 6 December 2019 there were 3,783 women in prison in England and Wales.189 7,278 women entered prison in the year to June 2019 — either on remand or to serve a sentence. Many women remanded into custody don’t go on to receive a custodial sentence — in 2016, 60% of women remanded by the magistrates’ court and 41% by the Crown Court didn’t receive a custodial sentence. Most women entering prison to serve a sentence (80%) have committed a non-violent offence. More women are sent to prison to serve a sentence for theft than for violence against the person,

robbery, sexual offences, fraud, drugs, and motoring offences combined. The proportion of women serving very short prison sentences has risen sharply. In 1993 only a third of custodial sentences given to women were for less than six months—in 2018 it was nearly double this (62%).

9: Children in prison

The number of children (under-18s) in custody has fallen by 73% since its peak in 2006. They are also committing fewer crimes—with proven offences down by 77% over the same period. At the end of September 2019 there were 809 children in custody in England and Wales. 31 children were aged 14 or younger. Three in 10 children in custody in 2017–18 were there for non-violent crimes. More than a quarter of children (27%) remanded in custody were subsequently acquitted in the year to March 2018. More than a third (36%) went on to be given a non-custodial sentence. More than half of all children in custody (52%) are from a black, Asian or minority ethnic background. The drop in youth custody has not been as significant for BAME children—a decade ago they accounted for a quarter of the population (26%).

10: Poor regimes

Purposeful activity includes education, work and other activities to aid rehabilitation whilst in prison. The government published an education and employment strategy this year, with proposals on increasing the use of release on temporary licence; giving governors powers to commission education in their prisons; expanding vocational training opportunities; and improving employment outcomes on release. Just over a third of prisons (34%) received a positive rating from inspectors in 2018–19 for purposeful activity work—continuing the decline from half of prisons in 2016–17. Inspectors found that people continue to spend too long locked up in their cells—around a quarter were routinely locked up during the working day, and in some cases more than half. This is “leading to frustration, boredom, greater use of illicit substances and often deteriorating physical and mental health”.

Thanks to Andy Aitchison for kind permission to use the header image in this post. You can see Andy’s work here.

3 Responses

I’d easily add an 11th shocking fact. The appalling state of prison fabric which means a vast backlog in maintenance and prisons literally falling down. How do you even start to rehabilitate people or deal with mental health issues in these conditions? How valued do staff feel when they have to work in such conditions with probably the worse IT in Govt (though visitors from MoJ feel happy with latest tech in their hot little hands),

Hello!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

I hate you