When I first became involved in designing and developing large scale projects to tackle drug-related crime, I was surprised at the reticence of some local authorities and other statutory funders to get involved in payment by results schemes, particularly those funded by Social Impact Bonds. Councils were having to make cuts left, right and centre and here were reputable Third Sector organisations knocking on their door with innovative schemes to tackle entrenched social problems with private funding to boot. How could they say no? Over time, I have come to understand their concerns. This post explores the potential of SIBs.

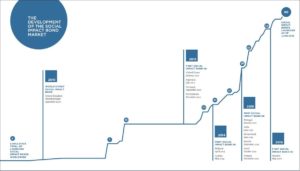

Social Impact Bonds are intended to be used to fund large scale interventions designed to tackle historically intractable social problems over a number of years. There is just one current UK example, the One project which provides a resettlement service to prisoners released from HMP Peterborough. However, the concept has created a lot of interest and the Office for Civil Society recently asked private and charitable investors to purchase social impact bonds worth up to £40m that will fund new schemes to support “problem families” in Westminster, Hammersmith and Fulham, Birmingham and Leicestershire.

Let’s have a look at how Social Impact Bonds work using the ONE Project as an example.

The ONE project (run by the St Giles Trust ) is funded to the tune of £5 million by a range of charitable trusts to help 3,000 offenders over six years. If it is successful in cutting re-offending rates, investors (the trusts) will see returns of between 7.5% and 13% per year from the Ministry of Justice. In the case of re-offending, the outcome metrics are developed so as to put a cost on a ‘reconviction event’ (more than one offence may be dealt with when an offender is convicted). This cost reflects the state’s expenditure in processing the offender through the criminal justice system and is substantial, particularly if an offender is sent to prison (which currently costs in the region of £45,000 per year).

If the St Giles Trust and its partners save enough reconviction events, investors make substantial returns – (one commentator speculates the payment per reconviction event for the ONE project is between £17,760 and £23,300). Although it should be noted that the maximum return on investment for the ONE project has been capped at £8 million. It’s not clear whether this includes inflation which, if it keeps running at the current rate (4% average over the 12 month period from September 2010 – August 2011), would add another £750,000 – £1,000,000 to the return. (For more details on the negotiation process see the initial evaluation report prepared by RAND for the Ministry of Justice.)

Now in the case of the ONE Project, paying for results is not a problem as the Lottery Fund (£5.25 million) and Ministry of Justice (£2.75 million) are footing the bill. But how would a local authority find the money? Obviously, the point of PbR schemes is that they save money from the public purse. However, in the case of re-offending, the savings are mainly to the police, court, probation and prison services which are funded by central Government.

The Ministry of Justice is running a number of PbR pilot schemes (Justice Reinvestment in London and Manchester, reducing re-offending at Doncaster prison with others in the pipeline). If these are successful, and the rumours are that Government ministers, especially Oliver Letwin, have invested high hopes that they will be, then a full roll-out is scheduled to begin in 2015.

So, what role will Social Impact Bonds play in funding a wave of public services commissioned via PbR? The people I have spoken to (civil servants, commissioners and providers) have a wide range of views. Some are very supportive, claiming that SIBs will attract large sums of money from philanthropists to fund innovative public services – a practice currently much more prevalent in the USA. Many are very taken with the idea of ordinary members of the public investing in public services both to do good and to make a profit – ‘impact investing’, as it is commonly known. Others take an opposing view, highlighting the fact that if schemes are successful, then the outcome payments come out of the public purse and are necessarily higher given the need to provide investors with a return on investment and the costs incurred in developing the financial instruments themselves (not that traditional public procurement is an inexpensive process). Matthew Taylor, Chief Executive of the RSA, writes in a recent post that few of the policy analysts he has consulted think SIBs will become commonplace.

I sense that the Government is politically very attracted by the notion of SIBs whilst Whitehall is more sanguine, quite happy to leave their development to the market in which case they could either become a mainstream funding instrument or end up being restricted to niche markets, perhaps focused on high risk ventures.

Given the current state of the economy and scale of the deficit, it is clear that there is likely to be a continued high level of interest in Private Finance Initiatives which is essentially what Social Impact Bonds are. At one level, those of us trying to tackle entrenched social problems like drug-related offending are not too concerned with the source of funding, we just want someone to ‘show me the money’.

3 Responses

Russell’s post summarises the main issues well. I want to make a couple of additional points

1. A difference between the One Project SIB and other PbR projects is that in the SIB model the private investors bear all the risk whereas in most PbR projects the risk is partly borne by the service provider. This seems to me to be a weakness for two reasons. Firstly, one of the arguments in favour of PbR is that the risk transfer encourages innovation and creativity on the part of the provider as well as increased responsiveness if the service is not delivering: this is lost in the One Project SIB model. Secondly, as a consequence of this first point, investors will have to be very confident that they understand how likely is the proposed service model of the provider to produce the required payment. However the data for most types of interventions is not robust enough to generate the level of confidence required: without this data how will investors be able to price that they are taking?

2. Russell makes the point that savings generated by, for example, reducing re-offending will accrue across govt agencies and thus will be difficult to secure by any one agency (the MoJ LA Justice Reinvestment pilots have this problem: the payment metrics for reducing offending relate only to MoJ cost savings). This is clearly a problem but there is a more intractable problem behind it – identifying cashable savings and securing them even within one govt agency is highly problematic. This is partly because of the problem of identifying causation within complex systems (would we have got this outcome in any case if the service wasn’t there? What else has changed in the external environment during the operation of the project?) but more simply getting the money out of the system is very hard. For example, the cost of a year of prison per prisoner is quoted as £35-40k per year. A service that could demonstrate it stopped 100 people going to prison for a year each would be unlikely to save MoJ a penny, far less the £3.5-£4 million implied in the headline cost per person. This is because, of course, MoJ would still have to pay for the upkeep and cost of existing prisons, staff etc. A service that could demonstrate that it stopped 1000 people going to prison for a year each and could show that this was sustainable would be a different story – then a prison could be closed down and real savings made, a proportion of which could be paid to the investor and/or provider. However this is a very hard test and I suspect many proposed PbR projects and/or SIB s would fail it

To make these points is not to say that SIBs are unworkable – personally I think the model has a lot of value in focusing attention and resources on intractable problems. However the cashability issue in particular needs to be worked through carefully

The Greater London Authority has just announced that it has been working with the Department for Communities and Local Government to develop a PbR scheme aimed at 650 rough sleepers which has to be funded via a Social Impact Bond: http://www.london.gov.uk/who-runs-london/greater-london-authority/directors-decisions/dd619

Thank you sharing your knowledge of social bonds. I find the concept remarkable and exciting for our society. I’d live to see more ideas like these take flight. I believe it is a more long term and effective solution to poverty in America. Thanks again.

Becky Purdy